July 1945, in some ways was like the lull before the storm. I remember my first experience of the eye of a hurricane passing over my home town. I was a small child and my parents told me about what would happen. Sure enough in just a moment we went from hurricane winds and lashing rains to an amazing stillness. We wandered outside just to feel the stillness and utter silence. In time and slowly, the winds picked back up to the full whip of hurricane winds. July 1945 is like the passing of the eye of a hurricane. The winds of Okinawa have quieted, the “divine winds” of the kamikaze are still … for the moment. And the world waits to see if the winds of the Asia-Pacific war will roar back with the advent of Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu.

Analogical imagining aside, there were key events that continued to play out in the month of July, both on the battlefield and behind the curtains in the halls of allied and Japanese governance.

On the battlefield, July was the month when Luzon was declared secure and the government of the Philippines resumed its role in restoring some measure of peace and restoration for the war torn island nation. Far afield from the Central Pacific, a major campaign was initiated for the capture of Borneo led by the Australian Army with assistance from allied nations. Borneo was first invaded by the Japanese in December 1941. Combat ended with the final surrender of allied forces in April 1942. The island nation was strategically important as it lay on the sea routes between the oil fields of Sumatra and the Japanese home islands. It was also a source of oil and food exports for the home islands.

The stories of occupation, guerilla warfare, prisoner of war camps, privation, and all the hallmarks of Japanese rule and brutality are a story for another time. But in July 1945 the allies launched the last amphibious landings of the Asia-Pacific War in the Battle of Balikpapan. The Australians were making great progress in the liberation of Borneo when the war ended on August 15th. The Japanese garrison surrendered and the island nation began its long road of recovery.

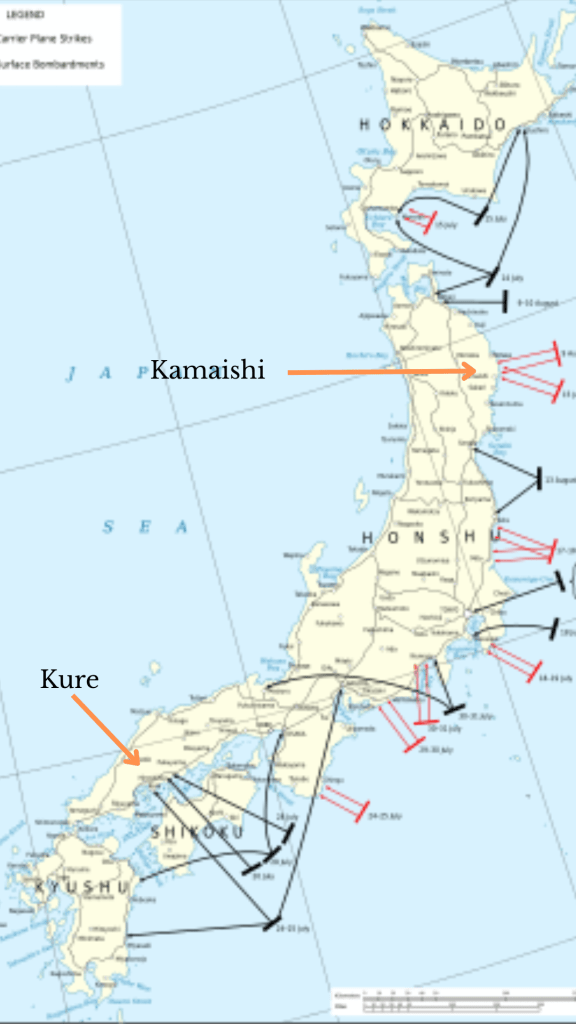

Meanwhile the B-29s continued the strategic bombing campaign over Japanese industrial sites and cities. By July targets were becoming fewer and fewer. The three major attacks were against the cities of Sendai (railway center), Kure (naval headquarters of IJN), and Fukui (railway center and war production). In addition the allies heavily bombed the Japanese ferry system connecting the islands of Hokkaido and Honshu, sinking eight ferries and heavily damaging two others. This attack, a significant part of the campaign to cripple Japanese industry, effectively ended the transport of vital coal from Hokkaido and severely impacted Japanese production.

Allied naval forces began a massive shore bombardment campaign against Japan’s main islands. The principal targets were the ironworks at Kamaishi and the industrial facilities at Muroran and Hitachi. But the real impact was on the morale of the civilian population as it not pn;y instilled fear, but convinced many that the war was lost. Unlike air raids where bomber squadrons would eventually pass, the people could see the Allied armada just off the coastline as that fired at will upon the ironworks. For a population that believed itself remote from direct assault, the sudden appearance of Allied warships off the coast, with no effective Japanese military response, was a stark indicator of Japan’s impending defeat. The bombardment undermined the credibility of the government’s wartime propaganda. Kamaishi was just one of many such events. As a result, many coastal cities were virtually depopulated as tens of thousands of civilians fled in panic. As a secondary effect, industries that were able to continue found absenteeism a major problem and had reduced productivity among traumatized workers that remained. In addition, mass evacuations from bombed cities like Kamaishi spread discouragement and disaffection for the war into rural areas, where many had previously felt safe. The influx of city evacuees, who were noticeably low in morale, further weakened the national resolve. While civilian attitudes had questionable direct influence on the government’s decision to surrender, the bombardments cemented the view among many citizens that the war was hopeless and invasion imminent. Wartime propaganda had raised the spectre of the rape and pillage of Japan once allied soldiers landed on the home islands.

The stories of Japanese conquest in 1942 were distant memories. The accounts of the war from 1943 and 1944 were sanitized and made to sound as though the allies were being held at bay, but by December 1944 air attacks from the Marianas against the home islands had begun, defeats in the Philippines had been suffered, and the home food situation had deteriorated. Morale of the home population was sliding. At the start of 1945, 10 percent of the people believed Japan could not achieve victory. By March 1945, when the night incendiary attacks began and the food ration was reduced, this percentage had risen to 19 percent. In June, when the fate of Iwo Jima and Okinawa became known, it was 46 percent, and just prior to surrender, 68 percent. (United States Strategic Bombing Survey Summary Report on Pacific War).

All of the above was a coordinated operation of air and naval resources as seen in the following graphic. The red indicates shore bombardment with the black indicating aircraft carrier air strikes.

The reason for Nimitz’s insistence on this range of attacks had several goals: to keep the pressure on Japan, continue to reduce the means of war production, targeting of any potential base for future kamikaze operations, eliminate the IJN as a viable attack force against Operation Olympic, and show the Japanese coastal population that the US Fleet could operate with impunity with sight of the home islands.

During this period land forces – US Army and Marines – were preparing for Operation Olympic. New recruits and European theatre (ETO) forces needed training and integration into experienced Pacific theatre (PTO) divisions, regiments, battalions, companies and platoons. The modality of fighting in the Pacific was very different from the ETO.

In parallel, the largest logistics supply operations the world had ever seen were already in progress as massive amounts of fuel, ammunition, clothing, vehicles, hospital/medical supplies, aircraft, assault vehicles (land and sea), food, … and list goes… were being shipped from west coast ports to the Mariana Islands and the Philippines as first stage depots for subsequent shipment to second stage depots at Okinawa where ports, floating depots and “beach dumps” were prepared and organized. And this is for the ground based troops and air units. The naval side of operations required all the necessary supplies to be on supply ships to support underway replenishment of all needed supplies.

Diplomatic Efforts

On July 8th the Supreme Council proposed and Emperor Hirohito approved the Fundamental Policy (Ketsugō Hōsaku) which reaffirmed the Ketsu-Go plan to continue the war. This was in response to the fall of Okinawa (June 22). But according to the official minutes (Sugiyama Memo and postwar testimony), the Emperor was not silent, but remarked: “I desire that you give careful thought to the ways and means of ending the war, in order to relieve the suffering of my people.” This was not a veto of the policy, but it was a pointed reminder: even while approving a fight-to-the-end stance, Hirohito was giving evidence that there was an acceptable alternative to Ketsu-Go. Nonetheless, the key point of the document moved forward: Japan would prosecute the war with all available resources, even if it meant the nation’s destruction. The leadership accepted the possibility of “100 million dying together” (ichioku gyokusai, “honorable suicide of the whole people”). The leadership then mobilized all civilians and military forces.

It was at this juncture, on July 9, that Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Kido Kōichi presented his memorandum to the Emperor in a private meeting: “Draft Plan for Controlling the Crisis Situation” (Kokunan Shori no Shisaku-an). Kido was not a member of the Supreme Council (the “Big 6”) but was highly influential. Kido had been covertly meeting with retired Japanese officials considered wisdom figures as well as influential professors from Tokyo’ universities. Prince Konoe was also a confidant to Kido’s developing thoughts.

The “Draft Plan” represents the first systematic proposal from within the Emperor’s inner circle urging him to personally lead Japan toward peace before the nation’s total destruction. By early July, Soviet neutrality appeared to be wavering and air raids were devastating Japan’s cities. Kido sensed that the military leadership would never seek peace on its own and that only the Emperor’s direct intervention could bring about surrender.

Kido’s goal was to avoid the complete destruction of Japan by continuing the war and most importantly to prevent the collapse and erasure of the kokutai, the Emperor-centered national polity. To achieve both, he proposed that the Emperor take the initiative to end the war through diplomacy.

The original document was never formally published but its full text survives in Japanese archives and has been cited by many historians. Richard B. Frank’s book, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (1999) provides a summary with key quotations.

Kido opens by acknowledging, in strikingly direct language, that Japan’s situation is hopeless: “Our national strength is exhausted; the war cannot be won. If the conflict continues, the nation will be destroyed.” He warns that the Army and Navy, despite their rhetoric, no longer have the capacity to repel invasion or defend the homeland. Kido argues that continuing the war will lead not only to physical destruction but also to the loss of the kokutai itself: “If we persist in fighting, it will end not in the preservation of the national polity, but in its collapse. The fate of the Imperial House will be imperiled.” In other words, obstinacy would bring the very outcome the militarists claimed to be fighting to avoid. Kido insists that the Emperor personally must act to change policy, since the military leadership will never yield on its own: “At this stage, no one but Your Majesty can resolve this crisis. A decision of the Throne is imperative.”

Unfortunately, Kido proposes that Japan approach the Soviet Union to mediate peace with the US and Britain, since the USSR remained formally neutral. Kido suggested that the Emperor send Prince Konoe as a personal envoy to Stalin. As discussed in Japanese-Soviet Diplomacy, that was a “dead end” whose net result was that no serious diplomatic effort ever reached the US or Britain.

Kido was the first to understand that unconditional surrender was the stated policy of the Allies and even before the Potsdam Declaration, he recommended that Japan accept defeat but seek to secure ameliorating conditions. He recommended three conditions: preservation of the Emperor and kokutai; autonomy in internal governance; and possible leniency regarding war crimes and occupation. He specifically warned against asking for retention of lands outside the home islands of Japan.

Kido urges immediate action, stressing that every week of delay increases the risk of national catastrophe, civil disturbance and a communist revolution should the Soviets enter the war and invade: “If decisive action is delayed, it will be too late. The collapse of the national polity would be unavoidable.” Kido counseled the Emperor to summon the Supreme Council to make clear his personal wish to end the war through diplomacy.

Kido reported that the Emperor agreed in principle. While he instructed Kido and Foreign Minister Tōgō to pursue contact with the Soviets, he did not call an Imperial Conference with the Supreme Council and Cabinet. As we know the diplomatic efforts failed, but the memorandum served to pave the way for the Emperor’s decisive intervention in the Imperial Conference of August 9–10, when he made clear it was time for peace.

Soviet troop movements. Between April and July 1945, the Soviets transferred approximately 1.5 million men, 3,700 tanks and self-propelled guns, 3,700 aircraft, 85,000 motor vehicles, and over 120,000 horses from the European fronts the border of Mongolia and Siberia facing Japanese occupied territories in China, Manchuria and Korea. This enormous movement was one of the greatest long-distance troop redeployments in modern history. It was in preparation for Operation August Storm when the Soviets declared war on Japan. By the end of July, militarily the Soviets were fully prepared for their invasion.

Potsdam. July 26, the Potsdam Declaration was issued. That was fully covered in a previous post.

The Eye of the Storm. July was a relatively quiet month – least in comparison to the intense battles of 1944 and early 1945. But in comparison to what was potentially coming – Operation Olympic – the winds of war were about to wheel back up to a Category Five storm.

Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.

Discover more from friarmusings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

And when the Kwantung Army surrendered to the Soviets, not one of the 100,000 Japanese soldiers saw home again.