The Japanese-Soviet story is more detailed than discussed in this series to this point. It is important to understand the “history” between these two Asiatic imperial powers. In the series to date, we picked up the “story” when the Soviets announced that they would not renew the neutrality pact with Japan in April 1945, giving the required one year notice that by April 1946 the pact would lapse. As previously noted, the Soviets were already transferring soldiers, transportation, armaments and ammunition to their “Eastern Front” – meaning Mongolia and Siberia. This was in accord with the February 1945 promises made to the Allies at the Yalta Conference when they promised to declare war on Japan within 3 months of Nazi Germany’s surrender. And all the while Japan was attempting to recruit the Soviets to represent Japan and broker an end to the war (detailed in Japanese-Soviet Diplomacy).

But why did Japan enter into a neutrality pact with the Soviets in the first place? Weren’t the Soviets part of the Allied war effort against the Tripartite Pact of Germany-Italy-Japan? Yes, but conflict with Japan and Russia (and then later the Soviet Union) had history in each country’s expansionist interests. Those interests included Korea, Manchuria, and Inner Mongolia.

An Imperial Collision in Asia

The Russian Tsars always held a vision of a “Greater Russia” that extended from west to east. With the completion of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the late 19th century, Russia sought economic and strategic footholds in Manchuria and Korea. This meant they needed ice-free ports on the Pacific (Port Arthur, later Dalny) to replace Vladivostok, which freezes in winter. At the same time, they saw the decline of the Qing dynasty and unrest in China as an opportunity to expand influence.

After the Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan rapidly modernized and adopted imperial strategies modeled on Western powers. For Japan the interest was raw materials, food imports to the home islands, and “room to grow” for the Japanese people. Japan needed to secure resources and strategic depth for its new industrial power. Korea was vital to its national security—“a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan” (per a common Meiji slogan) but strategic depth and raw materials widened the ambitions to Manchuria and beyond.

In 1895, Russia, Germany, and France forced Japan to return the Liaodong Peninsula to China after the Sino-Japanese War (a peninsula to the west of the Korean peninsula containing Port Arthur). For Japan this was a humiliation with its victory over China nullified by European imperial powers, especially Russia. The dagger was “twisted” in the wound three years later when Russia leased the returned territory from China in 1898, establishing Port Arthur as a naval base. To make matters worse during the Boxer Rebellion (1900), under the pretext of restoring order, Russia occupied Manchuria and was slow to withdraw. At the same time Russia began asserting control over northern Korea, despite earlier informal understandings that Korea would remain in Japan’s sphere.

Over the next several years tensions rose between the two nations, diplomacy started, stopped, stalled and fueled the rising tensions. Of primary importance to Japan was the formal recognition of its national interests and its preeminent role in the Asian world with an equal footing to European colonial powers. Japan proposed recognition of Russia’s dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of Japan’s dominance in Korea. Russia refused, offering instead to make Korea a neutral buffer and demanding Japan stay north of the 39th parallel which allowed Russian continuing control over Port Arthur.

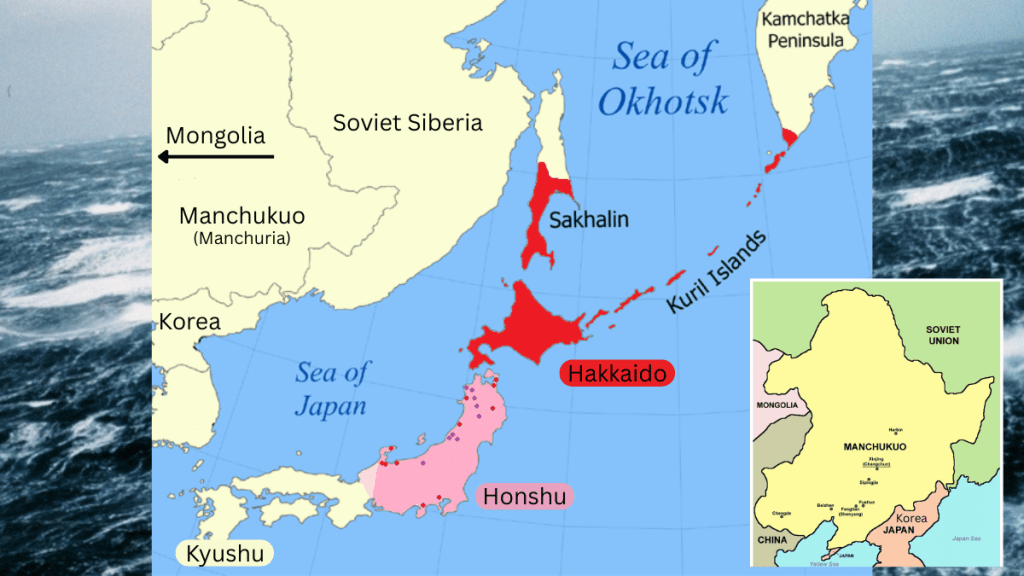

Russian diplomacy stalled negotiations while the Russians expanded troop presence in Manchuria. Japan interpreted this as an attempt to exclude it entirely from the Asian mainland. After months of fruitless negotiation, Japan broke off talks. Without a declaration of war, the Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur (Feb. 8, 1904). Japanese victory at the naval battle of Tsushima in 1905 ended the war. In the subsequent treaty Japan gained recognition of their special interests in Korea (which they annexed in 1910), southern Sakhalin Island, and lease rights to Port Arthur and the South Manchurian Railway. This was the first time an Asian nation defeated a European one in modern warfare. It changed the hierarchy of imperial power in the Asia Pacific region, established the Japanese military as the embodiment of the Japanese ideals and virtue, and fed the view of Japan’s destiny as leader, not just of the Asia Pacific but of the “eight corners of the world.”

Japanese-Soviet Conflict in the 1930s

By 1931 Japan sought to expand its dominance in Manchuria and northern China for economic and strategic security. Japan’s Kwantung Army seized Manchuria and established the puppet state Manchukuo. The Soviets, weakened by internal purges and economic strain, avoided open conflict but reinforced defenses in the Far East in order to preserve its influence in Mongolia. Both sides increased military presence along the Manchurian–Mongolian frontier. Another imperial collision was inevitable – only the scale of the collision was in question.

By 1935 small scale conflicts and cross border actions ratcheted up tensions in the region, so much so that by 1936 Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany identifying the Soviet Union as a common ideological enemy. In 1937 the Second Sino-Japanese War was fully underway. While the Soviets were not actors in the conflict, they were essential suppliers of arms, ammunition and airplanes to the Chinese forces – both Nationalists and Communists.

In 1938 there were growing border conflicts that led to a large-scale battle along the Manchukuo border with Mongolia. The action was initiated by the Japanese but Soviet–Mongolian forces decisively defeated the Japanese Sixth Army. This was a key moment in the years before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese Army recognized the limits of land war against the Soviets and as a strategic consequence the Army (Kwantung faction) was humiliated allowing the Navy to gain influence.

The Strategic Fallout

The result was a Japanese strategy focused on expansion toward Southeast Asia and the Pacific instead of northern expansion into Siberia. As for the Soviets, they undertook a “wait and see” attitude as the rise of Nazi Germany complicated their western borders. In August 1939 the Soviets agreed to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany. This pact guaranteed that neither country would attack the other, and for the Soviets was a strategic piece to avoid a two-front war. This was followed by the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact (April 13, 1941) in which both sides pledged mutual neutrality and respect for territorial integrity of Mongolia and Manchukuo – the other piece the Soviets needed to avoid a two front war. But it also served the same purpose for Japan as it pursued its plans to expand into Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Four Years Later – August 1945

With Nazi Germany defeated, the Soviets were not at war. All was quiet of their Western front facing Europe – the first Berlin crisis was almost 3 years away. All was busy on their Eastern front facing Japanese occupied Manchuria and Korea as Soviet troops, tanks, artillery, and supplies amassed opposite the Japanese Kwantang Army – once the pride of the Imperial Japanese Army, but not a shell of its former self with its resources transferred to fighting the allied advance in the Central and Southwest Pacific.

The Soviet’s imperial aspirations in the East had not changed since the 19th century – their 1945 entry into war against Japan was the fulfillment of a promise to the U.S. and Britain and a reason to do what they always intended to do: occupy Manchuria and Korea. In history, they took advantage of the bombing of Hiroshima and formally declared war just hours before Nagasaki. Historians seem united in their view that it was a rushed decision as regards timing because they wanted to declare war before Japan surrendered. Otherwise, their August Storm plan was pointed at the last week in August.

As mentioned in a previous post the outcome in Manchuria was not in question. The odds and manpower were overwhelmingly in the Soviet’s favor. The Soviets captured about 2.7 million Japanese nationals with 1/3rd of them civilian. The dead and permanently missing numbered ~470,000.

Beginning immediately after the surrender, the NKVD (Soviet secret police) organized the mass transfer of Japanese POWs to labor camps across the USSR. Between 500,000 and 600,000 Japanese soldiers and officers were deported to Siberia, the Urals, Kazakhstan, and other regions as slave labor. The Soviet reasoning for the internment was framed as legitimate war reparations—compensation for Japanese aggression in 1904–1905 and in the 1930s. While in the gulag-like conditions, between 50,000 and 100,000 died from conditions of forced labor, poor nutrition, disease, and other causes. Repatriation of soldiers began in late 1946 with the release of 400,000 POWs and continued off and on until the mid-1950s. In the end, tens of thousands were never accounted for.

Around 1.5 million civilians were stranded in Manchuria. Thousands were killed in the chaos following Japan’s surrender due to Chinese revenge attacks, bandit raids, and Soviet troop abuses (looting, executions, and rape, particularly in the first weeks). Women and children were especially vulnerable. There are remembrances and contemporary Japanese accounts that speak of mass assaults and suicides. Repatriation of civilians began in late 1946 and continued until the mid-1950s.

These numbers are the history and most view that our counter-factual history would have turned out the same way. The primary question that is unanswerable is whether the Japanese would have invaded Hokkaido – would the allies let them? – and would the Soviets have advanced to northern Honshu? It is clear that the Soviets did not have amphibious capability to sustain an invasion.

That being said, it is hard to know the effect of the Soviet declaration in our scenario. There are historians such as Tsuyoshi Hasegawa’s [Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (2005)] that hold, absent atomic weapons, the Soviet invasion into Manchuria would have galvanized the Imperial Japanese Army to overthrow the home government, declared martial law, and continued the war – not only waiting for the invasion of Kyushu but unleashing widespread warfare in part of Southeast Asia where their armies still maintained control. There is no feasible way to estimate the increase in civilian deaths except to note that the already horrific numbers of lost non-Japanese Asian lives (and Japanese lives) would only become horrific at a new level.

Image credit: Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.

Discover more from friarmusings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.