This is the last post in this series in which we explored the War in the Pacific…for the time being.

Along the way, it became clear that it was really the Asia Pacific War and had started in 1937 when the imperial ambitions of the nation of Japan launched military action against the nation of China, a conflict that had been simmering since 1931. We traced the rise of Japanese militarism that served as the agent of their colonial ambitions. When their 1939 forays into the border areas of Soviet controlled Mongolia and Siberia were easily repulsed, Japanese attention and planning turned to the Southeastern Asia region. If Korea (annexed in 1910) and Manchuria served as a food basket and new homesteads for an exploding Japanese home population, then Java, Malay, Borneo and other nations served as lands rich in oil, rubber, and other materials needed for their military-industrial complex. There was a strong sentiment among Japanese leaders that their national destiny was to be the rightful leader of the “Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” It was an ideology that was part of the education system and propaganda from the 1920s onward. It was not to free other Asian nations from the colonial rule of European nations, but to establish themselves as the new colonial master.

The early December 1941 charge across Southeast Asia ultimately led to the deaths of 30 million Asian civilians – and no small measure of war crimes known (Nanjing, Shanghai, Manilla, and more) and unknown. It was not the case that only a small platoon or company of Imperial Japanese soldiers were out of control, its prevalence across time and nations leads one to conclude it was an understood policy among field commanders. Was it the classic forage and pillaging of invading armies or was it also rooted in the notion of nihonjinron (theories of Japanese uniqueness). It was a view that underpinned a broader societal view that placed Japan at the center of Asia and devalued neighboring peoples as lesser people.

The series did not follow all the allied actions in the Central and Southwest Pacific areas, nor did it explore the details of the campaigns in the China-Burma-India (CBI) area. The series tried to point out critical U.S. military encounters with the Japanese that would shape next-step strategy but also inform the war planners on what were the military and socio-political factors needed to be overcome to end the war. Two early posts, Saipan and Battles that changed the War, gave an early indication of the bushido spirit that was present in Imperial soldiers, but also in Japanese civilians, and later in their kamikaze squadrons. The battlefield experience was that less than 3% of Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) soldiers surrendered or were captured. On Saipan and Okinawa, the Army and Marine encountered non-uniformed civilians participating in armed combat. This included women and children. In both battles, allied soldiers witnessed civilian suicides as the alternative to “capture” by the enemy. Such was the indoctrination.

The focus of the series then shifted to considering the role of Emperor Hirohito, the Supreme War Council, and other key leaders in control of Japanese war governance. The early September 2025 posts were extensive and meant to let the reader understand the inner workings of the wartime governance of Japan and the role of Emperor Hirohito. Post-war accounts in the more immediate aftermath of the surrender present the Emperor as constitutional monarch, preventing from interfering with the governance of pre-war and wartime Japan. As time marched on and more accounts were made available, a picture emerged that constitutionally he was in fact the supreme commander of all armed forces, and had considerably more leverage in non-military governance. His role in the continuation of the war with China and the attack on Pearl Harbor and across Southeastern Asia that brought the U.S., Britain, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands and other countries, is debated by historians from the west, China, and Japan.

But is clear from the historical record is:

- Cabinet and Supreme War Council recommendations to the Emperor must be unanimous and if unanimity can not be reached, the government collapses and a new cabinet and council must be promoted.

- In accord with the Meiji Constitution, certain cabinet members must be filled by active duty members of the military. In the context of #1 above, this means that the military held a de facto veto on anything with which it does not agree. A single military member can either “filabuster” or simply resign – either achieve the same thing: collapse of the government.

- In accord with the Meiji Constitution, the Emperor is a Constitutional Monarch, but at the same time is “Supreme Commander” of the Military (daigensui). Yet he seemed to operate out of a self-imposed neutrality at times and at others was actively involved at strategic level planning.

- There was a strong current of ultranationalism among the Imperial Army staff and field officers deployed. There was no assurance that they would follow orders to lay down arms since they had ignored orders and instigated armed conflict and operations from Manchuria to New Guinea and beyond. Decisions in the field were often made by majors and colonels based on their view of national priorities. In 1937, there were cases when direct orders from the Emperor were ignored.

- There was a long history of military-led assassinations of political leaders in the 1920s and 1930s. The assassinations included Prime Ministers, Navy Secretaries and top governmental leaders.

In the middle of the milieu, decision making, pre-war and during the war, was pluralistic and consensus-oriented participation of ruling elites that resulted in ambiguous individual responsibility baked into a process of negotiation and compromise – this included the Emperor. There was no single desk where the “buck stopped.”

The one decision that needed to be made was some form of surrender. By January 1945, for all practical purposes Japan was militarily defeated. But then surrender is not a military decision, it is a political one. The post Behind the Curtain and others pointed out the lack of a political consensus and will to end the war. From late 1942 onward, Japan was “on the back foot,” suffering defeats on land and at sea. Despite that, the Emperor was assured that the decisive battle (win or lose) that would bring the Allies to the negotiating table was “next.” That was always the goal – negotiate an end to the war that left Japan as the colonial ruler of Southeast Asia, retaining a standing military, and with the kokutai – the Imperial institution in place. That was not the Allied goal.

The Allies’ experience of World War I made clear that an armistice or negotiated cessation of arms only “kicked the can down the road.” The allied intent was to win the war, occupy the nations, and rid Germany and Japan of any trace of the militarism that started the war – and to make sure that they knew they had been defeated so as to preclude the rise of the next generation problem such as the rise of Nazism in Germany in 1930.

As the war entered 1945 both sides were planning for the decisive battle – the invasion of the Japanese home islands. The Japanese planned Ketsu Go and as the end of summer drew near their plans took shape and portended a horrific battle. In parallel, the Allies prepared for the invasion with a naval blockade, unrestricted operations against Japanese merchant shipping by U.S. submarines, and a devastating strategic bombing campaign which included firebombing of Japanese cities, military installations and manufacturing centers. The latter of which grew more intense once US Army Air Forces could operate from Iwo Jima and Okinawa. This all part of a larger Operation Downfall Planning which continued to evolve in the face of intelligence operations that revealed a massive build up of forces on Kyushu that would oppose any landings. The June 1945 Downfall casualty estimates continued to grow at an alarming rate as the late July intelligence became available indicating Japanese troop strength ready to oppose any Kyushu landing force was now 3 times larger than any June planning estimates.

As discussed in last week’s posts, in our counter-factual where no atomic weapons are or will be available in 1945, the Allies still have to find a way to stop the war – and there are only bad options. There are no options that do not involve massive Japanese civilian casualties. But some option has to be found in order to stop the on-going deaths of non-Japanese Asian civilians across Southeast Asia.

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu, was planned for November but no later than December 1, 1945. In actual history, the weather at the beginning of November would have pushed the invasion until late in the month. In the interim the “blockade-mining-bombing” operations would have continued as discussed in The Unbearable End. The result of this approach without an accompanying invasion of Kyushu would like result in the following:

| Month | Expected Condition |

| Aug–Sep 1945 | Urban food ration breakdown begins; coastal transport essentially halted. |

| Oct–Nov 1945 | Coal shortages cripple industry and electric power; rail transport is minimal. |

| Dec 1945–Mar 1946 | Famine and disease on a nationwide scale; mortality potentially in the millions. |

| Mid–1946 | Economic and social collapse, food riots, and potential regime breakdown. |

In that post, I wrote:

“Assuming that the Japanese surrender on December 1, 1945, that still means the war continued for another 4 months (August thru November). Without an invasion, losses to the Allied military would have been minimal as Japan began to wither on the vine. If the estimates of blockade lasting until March 1946 yielded 6-10 million deaths due to starvation and disease, what would be the effect by December 1945? Other famine studies suggest that deaths would have been in the 20-25% of total by the half-way point. That translates to roughly 1.4 and 2.25 million people in Japan. Outside Japan in the occupied territories, in the same 4 month period approximately 1 million non-Japanese Asians will die.”

“The resulting death toll of the blockade-mining-bombing (only) is projected to be between 2.4 and 3.25 million civilian deaths across the Asia-Pacific region. Truly an unbearable end.”

Would that have been enough to end the war? Would the collapse of Japanese society be enough to bring the Emperor to issue a Saidan, a sacred decision, to direct the Cabinet and Supreme Council to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration? Would the advance of the Soviets in Manchuria changed the minds of Japanese leadership? Would the Soviets attempt a larger scale invasion of Hokkaido?

August 1 – December 1, 1945: the death toll

These numbers reflect continued blockade and bombing, Soviet operations in Manchuria, the Kyushu invasion, and continued Japanese action and occupation across Southeast Asia.

- Allied military – 100,000 but, in addition, another 115,000 allied POWs would die by either execution or starvation. (note: there were no reliable numbers for Soviet losses in Manchuria)

- Japanese military losses in Manchuria and on Kyushu – 1.0 to 1.5 million with another 200,000 dying in Soviet gulags after the war.

- Japanese civilians – 1.9 to 2.75 million

- Asian civilians outside Japan – 1 million

For just the period Aug 1- Dec 31, 1945 the death toll is estimated at 3.4 to 5.75 million people.

As noted, there were only bad options.

No End in Sight

The historian Richard Frank tells a story in his book Downfall about a history symposium in the late 1990s that was meant to cover the breadth of the war in the Pacific. He sat with a noted Chinese historian as together they listened to presenter after presenter talk about the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was as though that was the only topic that mattered. The presenters’ views were extremely narrow – both for and against the use of the atomic weapons. All presented the topic as only a Japan-Allied confrontation. There was no recognition of the tremendous human suffering and death brought about by Japanese aggression across Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. No recognition that the war started before December 7, 1941. Without intention they continued a trend that, by its singular focus on three days of the war in August 1945, unknowingly devalued the humanity of millions and millions of Asians outside Japan. Further, the arguments against the atomic weapons to end the war, never considered the other options to end the war, even in terms of Japanese civilian lives. The majority of the presenters at the symposium were either western or Japanese. When lessons of the past are lost, then consideration of the future becomes even more narrow.

As part of the series I also included several posts on Just War Theory. I had the same kind of impression as Frank and the Chinese Scholar: an extremely narrow view. To be fair, I did not do the same kind of research as with the other aspects of the series, but I found no fruitful leads to continue the search. All the moral theologians and theorists that were accessible to me, after their extended writing, simply concluded that the use of the atomic weapons was immoral and not allowed in the just war tradition. Like the historians above, none of them considered the options to end the war. None of them addressed the wholesale slaughter of civilians up to August 1945 and the moral implications of not stopping the war as quickly as possible. Too many of them pointed to international agreements that were absolute: civilians could not be targeted in war. In 1945 such agreements did not exist.

Nor do they fully exist now. Article 51(5) of Additional Protocol I of the 1977 Geneva Conventions prohibits any “attack which may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.” The absolute prohibition against civilian deaths does not exist in law or convention. The incidental loss of civilian life is held “in the balance” against “direct military advantage anticipated.” The intended targeting of civilians for no other reason than to target them is prohibited. But often war has no intention but civilian deaths happen.

That was not an argument for using atomic weapons. That is something others can take up.

The whole series is also not an argument that “if you don’t want to face a catalog of bad options to end a war” then don’t participate in warfare in the first place. The history of humanity is that even peaceful nations are not given such neat options. There are nations and non-state actors that have their own vision of the way the world should be: a greater Asian prosperity zone free of European powers, a greater Russia, a Roman Empire, a Mongolian Empire, and the list is far longer. And it is always the case that there is a vision held by a small cadre of people that leverage their aspirations upon the people of a nation so that the people see “their destiny.” And somehow that destiny often crosses recognized borders sometimes drawn without regard to peoples. For every Ukraine there is always Russia.

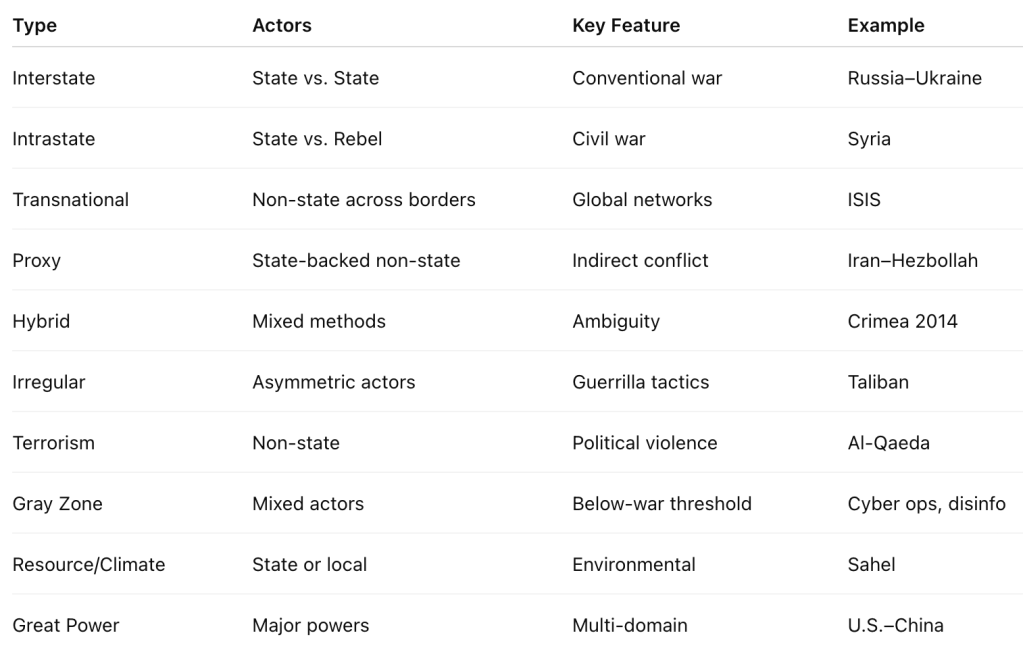

Will there be a World War III? I hope not. But then the nature of war is changing. The battle space remains in the world and now exists online. Nations will battle national; other nations will take sides. Some wars are internal to a nation casting a group as terrorist or patriots depending on one’s point of view; other nations will fund one side or the other. Warfare is increasingly urban which inevitably leads to civilian deaths. More and more women and children, out of uniform, are involved in warfare. Even the vocabulary of warfare is evolving:

After the war, though the atomic bomb has understandably dominated Catholic just war reflection, a number of Catholic theologians reflected more broadly on World War II through the lens of just war. Figures such as Jacques Maritain, Romano Guardini, Johannes Baptist Metz, John Courtney Murray, and Yves Simon uniformly agreed that the war against Nazi Germany and Japan met the just war criteria jus ad bellum – but each also questioned the known effects of strategic bombings, intentional fire bombing, and failure to discriminate actions against civilians as failures, jus in bello.

In this age there has been more attention on The Warfighter and the moral, spiritual, psychological burden brought about in the events they expected to encounter and events that were not part of what combat was supposed to be about. Some also carry the burden of being unable to provide medical aid to a wounded comrade or freezing during a dangerous moment. And there can be moments when one wonders if the toll and sacrifices are not valued or understood by the civilian population. One wants to go home, but worries if they can “go home.” When you read the post-WW II theorists the focus was clear: the burden on the war planner. When one reads the current theorists the burden seems to have fallen on the warfighter – the one whose world consists of himself and the men and women in his unit. It is a small world the warfighter tries to save.

While allied forces completed the battle for Okinawa, naval units continued the blockade, bombing continued as did the Japanese occupation and subjection of Manchuria and parts of China, Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia), Burma (Myanmar), Malaya and Singapore, Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), other smaller locales. Borneo’s liberation was underway as was the Philippines. This was the Asia-Pacific war that needed to stop. The root cause of the war needed to be removed from power and the means to wage war.

In August 1945 there was no end in sight that had anything but bad options.

Thanks for reading.

Image credit: Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.

Discover more from friarmusings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this series Fr. George. I can’t imagine how much time you spent to research and write it. I learned many things, but the most surprising was the death counts in Asia. I had such a simplistic view of WWII in general -the Holocaust, Pearl Harbor, and the atomic bombs. Needless to say, learning about the Japanese culture, military, and their goals and failures was a real eye-opener.

Bill, you’re welcome.

Thanks for this series, Father George. It was very interesting and I learned a lot. The deep dive into what was happening in Japan gave me new perspective. Looking forward to your next series.

Scott, you’re welcome.

Thanks for writing this series Fr. George. It was most informative and provided an insight to the Japanese high command that was most enlightening.

Rich, you’re welcome. Go Canes!