Today we celebrate the Feast of the Holy Family. We’re not celebrating “perfect family Sunday.” Offered as a point of humor, let us remember Jesus was without sin and Mary, by God’s grace, was kept free from sin – no such claim was made for Joseph. He wasn’t perfect, but he was holy. And so we celebrate and consider holiness this Sunday as we are all called to remember that it was into a family that God sent his Son. A family that has its ups and downs, joys and sorrows, agreements and disputes, and all the things that are tossed into the cauldron called family life. A family like yours in many ways. A family that was holy, not perfect. My point being, that holiness lives and grows apart from perfection and perhaps even thrives best among the flawed and messy. And in family life, that means something far different than a Norman Rockwell painting.

Consider the early life of the Holy Family:

- Joseph and Mary are betrothed one moment, and the next Joseph finds out Mary is with child and not his. But with God’s grace they work through it.

- Next, circumstances made them vagabonds on the road, arriving in a town with no room at the inn. A cave would have to suffice.

- Jesus is born, wrapped in whatever cloth was around, and laid in a feed trough.

- The local power, King Herod, is trying to kill them

- They are on the run, heading to Egypt as refugees, probably using the gold, frankincense, and myrrh for bribes, border crossings, payoffs, and to settle in a foreign land

- When they return, they seem to settle in a new town and have to start all over in another part of Israel, Galilee to be specific, that was the butt of many disparaging remarks. They ended up in Nazareth which was no more than a wide spot on the road.

- Joseph seems to have passed his trade onto Jesus, but we really do not know too much. Joseph seems to disappear from the Biblical narrative relatively early during Jesus’ childhood – it is almost has though Mary, at some point, was a single mom raising Jesus.

- For the first 30 years, Jesus seems to have lived a sedate life in Nazareth – and no doubt Mary wondered about the messages of the angels, the prophet Simeon, the visit of the Magi, and all the things that proclaimed her Son to be Messiah.

- And then Jesus enters public life – what was she to think. There is a scene in which the disciples interrupt Jesus to let him know that his mother is outside and wants him to come home.

Hardly a portrait of a perfect family. But a family that is together through the very turbulent cauldron of their life. I do not think too many people are going to volunteer to travel the same path to holiness in their family. No matter what path, family can be a cauldron where hearts and souls are tested.

But here’s the thing about families: everyone is part of one. You choose your friends, not your family. Still family isn’t for you. It is all for others in the family. Listen again to the words of our reading from the Letter to the Colossians – it is a blueprint for making family holy no matter whatever form or shape you find yours – and it is neither simple nor easy – but it is graced.

as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved – Begin by remembering you are loved. Recall your faith in God and Jesus – that alone makes you hagios – a holy one. Admiral William McRaven gave a commencement speech in 2014 that became a book: Make Your Bed. His advice was, first thing in the morning, before all else, make your bed. And you will have already accomplished something at the beginning of the day. I would amend that advice: remember you are holy and beloved…and then make your bed.

Put on, …. heartfelt compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness, and patience, bearing with one another and forgiving one another: Put on… in other words, it will take an effort. Part of the effort might be that you are being called to be/do other than what you feel. Compassion and all the rest might be a universe away, or seem that way, amidst all the turbulence and turmoil in your heart.

Think about patience: “Patience is a virtue.” We’re all familiar with that expression, and many of us know that patience is listed by Paul in Galatians 5:22-23 as among the fruit of the Spirit. So, there’s no disputing that the Christian ought to be patient. But what about impatience? Is it a sin? I would suggest it is a temptation but remember this: all such moments are ever surrounded by the grace of God in superabundance. You just need to remind yourself to choose grace – and where patience is lacking, compassion, kindness, or gentleness can take its place.

The 19th century theologian, Maurice Blondell, suggested that in the moment you most feel like striking out at another who has offended you, worn out your patience or any other manner of annoying thing – in that moment, to choose charity, is perhaps the most Christian you will ever be. In that moment you have chosen to follow Christ instead of yourself. Blondell goes on to write, in essence, that just keep doing such virtues and you will become those virtues. Your thoughts become your actions, which become your habits, which form your character, which leaves you as the person you have become.

if one has a grievance against another; as the Lord has forgiven you, so must you also do. No one earns true forgiveness, it is always a gift. Give it away. There’s more!! If you pause for a moment it is not too hard to dip into our own memories and experience to recall a time when we had been wronged and we were just not able/willing to forgive, or the forgiveness was so shallow that it did not take root and soon arose again into daily life. It is not too hard to imagine those moments in our lives as moments of darkness with not a whole lot of light able to penetrate and shine in. Poetically it is as though those times are as being imprisoned by hurts and our lack of forgiveness. We are just unable to set down the burden of all that marks those days and nights. Meanwhile, the other person is probably not giving the matter a second thought, just moving through life unburdened, free. …and then you meet the other person. Be charitable in the moment remembering you have been forgiven. So pass on the gift.

And over all these put on love, that is, the bond of perfection. Despite what Hallmark Cards proclaims, love is a choice. Ask anyone who has been married for many years. They can all remember a time when they did not like the love of their life, but they chose to love: “love bear all things, believes all things, hopes all things, and endures all things. Love never fails…” But we have to choose to love, to make the effort, to “put on” love.

All of the above is to be your gift to your family.

What’s there for you?

Hopefully, your example helps create a home where those gifts are being given to you by others. Then you will know: And let the peace of Christ control your hearts… Even when you don’t feel peaceful.

And be thankful. Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly…. with gratitude in your hearts…

This is your family. It is one of a kind, warts and all. It is uniquely loved by God

Go do all these things, “put them on.” Be a holy family.

Here’s a question: heartfelt compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness, and patience – are we as family members holding that out to one another? We need to because Family is like a roller coaster – wonderful one moment, chaos and screaming the next, and a lot of hard work in between.

Holiness isn’t about feeling happy and having rosy memories. It is about love — the kind of love that is willing to suffer or die for the beloved. The kind of love Christ has for us.

First thing tomorrow: remember you are holy and beloved. Then make up your bed.

Amen

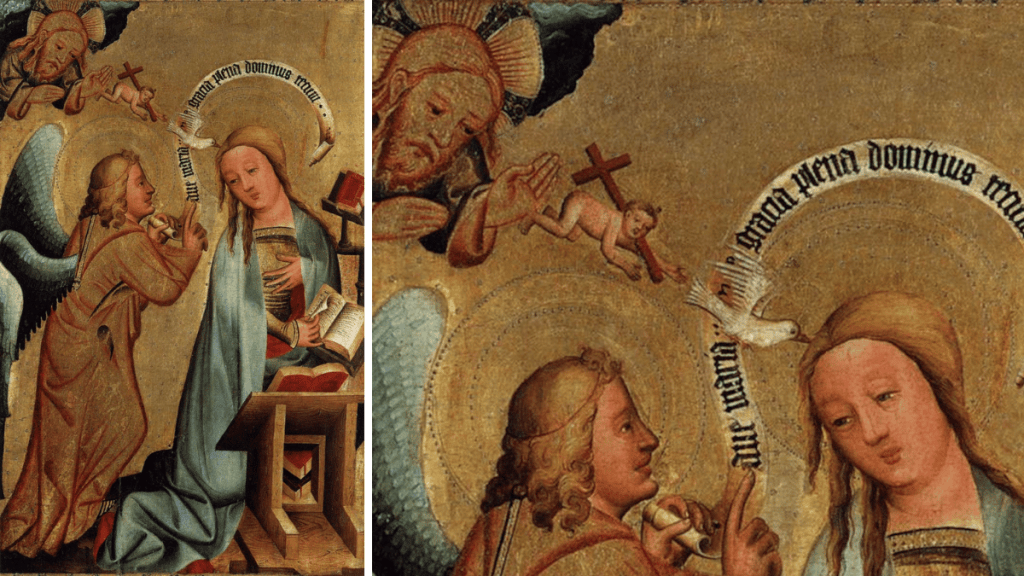

Image credit: Stained glass window, Sts. Joseph & Paul Catholic Church, Owensboro KY | PD