In May of 1942 the Japanese Empire covered 10 million square miles and extended from Manchuria, China and Korea eastward to the International Dateline and southward to the Philippines, Dutch East Indies, Java, Borneo, Sumatra and Malaya. The shape of the Empire was as though a lopsided, bottom heavy pear with Japan located at the top near the stem. As an island nation massively importing oil, rubber, iron, bauxite, aluminum, all manner of raw materials – and food – it was completely dependent on shipping to fuel the war machine, supply its armed forces, and feed the people on the home islands.

A blockade of Japan was, from the beginning of the war, a primary objective of the Allies. The island empire was surrounded by shallow, mineable water. Her crowded people depended on imports for 20 per cent of their food; nutritional standards were so low that a mere one-fifth reduction of imports meant privation for the population. Japan’s war effort and manufacturing potential depended on imports for 90 per cent of all oil, 88 per cent of all iron, 24 per cent of all coal. Over half of all domestic coal was waterborne between mine and factory. Even in-country domestic transport depended in large part on coastal craft transport because the geography of Japan made rail and road development problematic

On December 7, 1941 Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold R. Stark authorized unrestricted submarine operations against all Japanese ships – combatant or merchant. An earlier post on the topic described the slowly building strangulation of merchant shipping over the course of the war. By 1945, Japan no longer had access to 90–95% of the oil/fuel it had been importing. There were similar impacts of the other raw materials imported from the southern reaches of the Empire. By 1945 the open ocean sea lanes from Borneo, Java, Indonesia, French Indochina (Vietnam) and all points in Southeast Asia were heavily patrolled by American, British and Dutch submarines. As described in the Big Blue Fleet post, the fast carrier fleet and land based allied aircraft were beginning to take a serious toll on Japanese shipping. The cumulative effect was a slow tightening of the blockade.

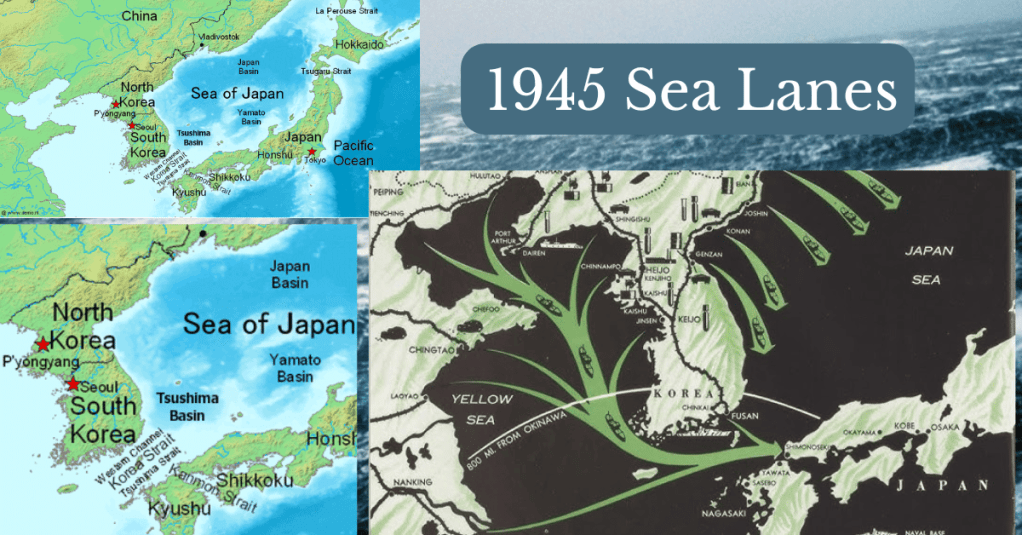

The submarine blockade had virtually stopped water-borne traffic to and from the huge east coast ports of Tokyo, Yokohama, and Nagoya but a vast amount of shipping still passed into the smaller west coast ports facing the Inland Sea (Sea of Japan) after passing through Shimonoseki Strait and the Bungo Suido. These were the only “safe” sea lanes: the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea, and the straits and inter-island passages within Japan. And even that was about to change.

Submarines already had been laying mines in the Sea of Japan and near west coast Japanese ports with some effect. The Sea of Japan was a dangerous operating area for allied submarines due to shallow water and lack of accurate charts. The Japanese still provided air patrols and combat coverage for shipping in the Sea of Japan and the Combined Fleet dedicated destroyers to merchant escort duty. Submarines could carry 24-40 sea mines, but that meant the submarines did not have torpedoes. Each patrol had to balance the torpedo/mine loadout. In late 1944 Admiral Nimitz requested that his naval operations be augmented by extensive mining of Japan’s “safe sea lanes” by the US Army Air Force (AAF) operating out of Tinian and Saipan.

Now that the B-29s had the ‘reach’ to cover the same area, they only needed the mission to drop mines in designated areas. They were far more capable of delivering large numbers of anti-shipping mines in short amounts of time. It took time for the AAF to agree to the mission and then to modify the B-29s for the mine dropping mission. Nimitz had hoped the operation could have commenced in January, as the attrition of enemy merchant shipping might have considerably reduced Japanese resistance by the time of the Okinawa assault.

The mining campaign of the safe sea lanes and non-East coast ports was initiated by the Tinian-based B-29s on 27 March 1945: Operation Starvation. The title was meant to convey the goal: starving Japan’s war machine of needed raw materials and oil, as well as starving people on the home islands who depended on the net import of rice and raw fish. Marine merchant traffic between Japan and the Asiatic mainland grew scarce. Manchurian imports dropped. Major General William F. Sharp, an American POW in Siberia, watched lines of loaded freight cars grow longer, waiting for Japanese ships which never came. The goods were available; the transport ships were not.

Factories which had survived continued strategic bombing raids operated at reduced levels or not at all. “It was not only the bombing of factories that defeated us,” said Takashi Komatsu of the Nippon Steel Tube Company, after the war was over, “it was the blockade which deprived us of essential raw materials— aluminum and coal.” Hisanobu Terai, president of NYK, Japan’s biggest shipping line, blamed food and raw materials shortages for the defeat and claimed that in the last months “proportions of shipping sunk were one by sub, six by bombs, twelve by mines.” The proportions were not technically correct, but the statement was indicative of the sense of the growing frustration and fear of the industrial sector of Japan’s war economy.

In addition to the havoc brought to bear on Japanese shipping, U. S. mines kept Japanese mine sweeping forces busy. At least 20,000 men and 349 ships attempted to keep sea lanes and harbors open during the blockade. Three out of every four minesweepers were lost. Speaking for all Japanese mine experts, Captain Kyuzo Tamura, Imperial Japanese Navy, told postwar interrogators, “The result of B-29 mining was so effective against the shipping that it eventually starved the country. I think you probably could have shortened the war by beginning earlier.”

Shipping losses continued, and seagoing traffic dwindled to a mere trickle. Merchants not sunk were in need of repair, but only 3 of the 22 principal merchant marine shipyards were open because access was closed due to sea mining. Damaged merchant ships were as good as sunk; there was no way to repair them.

Shortages of coal, oil, salt, and food were coming close to eliminating what Japanese industry survived the bombing raids. Japan’s leading industrialists could see the end coming. By mid-July they warned military leaders that if the war went on another year, as many as 7 million Japanese might die of starvation.

Mines sank or damaged over 670 ships, accounting for more than 1.25 million tons of shipping. Shipping through major areas like Kobe declined by 85% from March to July 1945

As an island nation dependent on outside sources of oil, raw materials, and foodstuffs, Japan was uniquely vulnerable to sea mine warfare. The AAF launched 1,529 sorties and laid 12,135 mines in 26 fields on 46 separate missions. A total of 670 ships were sunk or damaged, accounting for more than 1.25 million shipping tons.

Eventually most of the major ports and straits of Japan were repeatedly mined, severely disrupting Japanese logistics and troop movements for the remainder of the war with 35 of 47 essential convoy routes having to be abandoned. This operation sank more ship tonnage in the last six months of the war than the efforts of all other sources combined during the same period.

Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.

Discover more from friarmusings

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.