Reflections on Matthew 2:13-23

Alyce M. McKenzie

In her book Amazing Grace: a Vocabulary of Faith, contemporary Christian author Kathleen Norris contrasts the fear of Herod with the faith of Mary and Joseph.

Everything Herod does, he does out of fear. Fear can be a useful defense mechanism, but when a person is always on the defensive, like Herod, it becomes debilitating and self-defeating. To me, Herod symbolizes the terrible destruction that fearful people can leave in their wake if their fear is unacknowledged, if they have power but can only use it in furtive, pathetic, and futile attempts at self-preservation (Norris, 225).

The tradition of Herod’s “slaughter of the innocents” (Mt. 2:16-18), offers an account of the tragic consequences of such defensive, self-preserving, paranoid fear. This brand of insecurity never leads to anything good. Ironically it most often backfires, shrinking rather than enhancing the one who fears. Herod is a case study that proves the truth of the first half of Proverbs 29:25: “The fear of others lays a snare, but the one who trusts in God rests secure.”

In the process of fearing others, sadly, the one who fears seeks to douse the light of other lives and often appears to succeed. We could make a long list of the sufferings inflicted on others by those who in the past and today are both powerful and paranoid. We hold to the faith that such fear cannot douse the light of the world we celebrate at Christmas. This passage forces us to stay real—paranoid insecurity is a persistent force.

Norris points out that Herod’s fear is the epitome of what Jung calls “the shadow.” Herod demonstrates where such fear can lead when it does not come to light but remains in the dark depths of the unconscious. Ironically, Herod appears in the Christian liturgical year when the gospel is read on the Epiphany, a feast of light (Norris, 226).

Norris tells of preaching about Herod on Epiphany Sunday in a small country church in a poor area of the Hawaiian Island of Oahu. It was an area of the island that tourists were warned to stay away from, an area where those who served the tourist industry as maids and tour bus drivers could afford to live. The church had much to fear: alcoholism, drug addiction, rising property costs, and crime. The residents came to church for hope.

In her sermon Norris pointed out that the sages who traveled so far to find Jesus were drawn to him as a sign of hope. This church, Norris told her congregation, is a sign of hope for the community. Its programs, its thrift store have become important community centers, signs of hope. The church represented, said Norris, “a lessening of fear’s shadowy power, an increase in the available light.” She continued to say that that’s what Christ’s coming celebrates: his light shed abroad into our lives. She ended her sermon by encouraging the congregation, like the ancient wise men, not return to Herod but find another way. She encouraged them to “leave Herod in his palace, surrounded by flatterers, all alone with his fear” (Norris, 226).

There is the fear of Herod and there is the fear of the Lord exemplified by Mary and Joseph which, we are promised, is the beginning of knowledge and wisdom (Pr. 1:7). When we open our doors, even just a crack, to allow the fear of the Lord to enter in, we have taken the first step in a lifelong process of exchanging the fear of Herod for the faith of Mary and Joseph.

The fear of the Lord is the Bible’s code word for a full-bodied faith that includes trembling before the mystery of a Transcendent God and trusting in the tenderness and faithfulness of an imminent God. The fear of the Lord is the beginning of our being able to say, with Mary, “Here am I, a servant of the Lord. Let it be to me according to your word” (Lk. 1:38). It is the source of Joseph’s wordless obedience (Mt. 1:24) and Jesus’ words from the cross in Luke: “Into thy hands I commit my spirit” (Lk. 23:46). The fear of the Lord opens us to the comfort and stamina God offers even in times of undeserved and profound suffering. The fear of the Lord is the impulse that shuts our self-righteous lips when we look upon the suffering or mistakes of others. It impels us, rather than to retreat in cold judgment, to reach out with comforting, capable hearts and hands.

When we put aside our paranoid, self-centered fears and embrace the fear of the Lord, we face the reality of an unknown future with the good news that we are accompanied by a God who never abandons us. The shadows of fear are illuminated by the light—Immanuel, God with us!

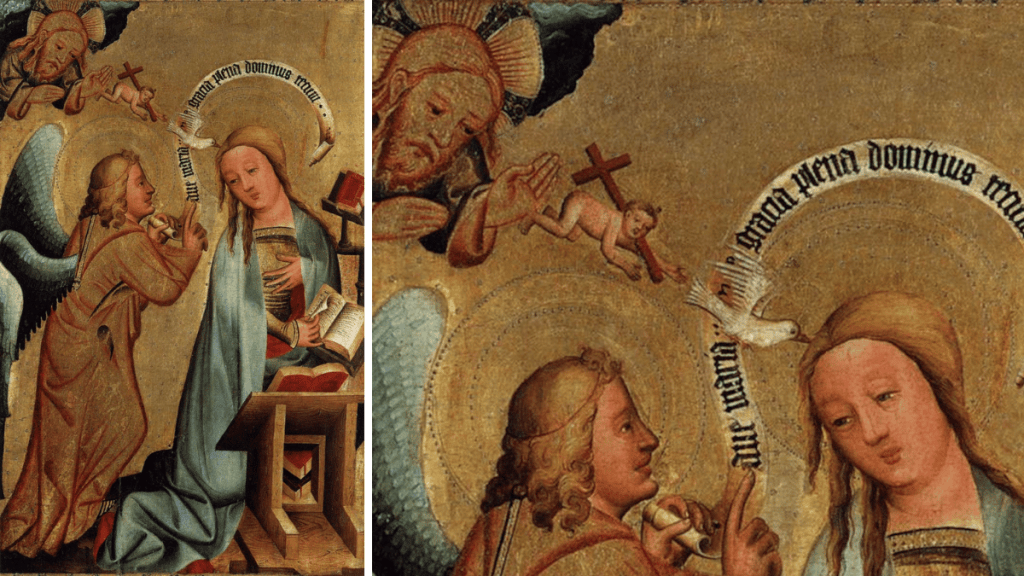

Image credit: Stained glass window, Sts. Joseph & Paul Catholic Church, Owensboro KY | PD