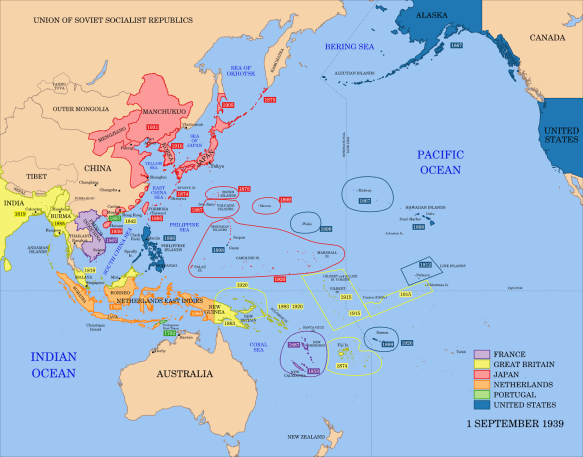

In the summer of 1939 Japan was increasingly bogged down in combat with China. As you can see in the map below, Japan controlled not only Manchukuo (Manchuria) but swaths of Inner Mongolia and China. Importantly, Japan also controlled almost all major seaports facing the East and South China Sea. Manchukuo presented its own control issues, largely centered around rampant banditry, but all the other areas required the Kwantung Army (Imperial Japanese Army on the mainland) to provide occupation and policing forces in areas they had conquered. At the same time the Kwantung Army continued offensive operations in Northern China.

Notice that Japan also had an extensive border with the Soviet Union as well as a history of conflict with czarist Russia that extended some 60 years back in time including the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War which removed Russian presence in Manchuria and Korea. Russia lost the warm water ports in Darien and Port Arthur, access to the resources of Manchuria, and was often required to transport goods and resources via the Trans-Siberian Railway rather than via ship. In addition Russia was required to cede the lower half of Shanklin Island (just north of Japan). All of this fit into Japan’s “strategic buffer” concept keeping China and Russia/Soviet Union at “arm’s length” from the home islands.

The Nomonhan Incident

Also known as the Battles of Khalkhin Gol, the Nomonhan Incident was a major but undeclared border war fought between Imperial Japan and the Soviet Union’s Mongolian forces from May to September 1939. It occurred along the poorly defined frontier between Japanese-controlled Manchukuo and Soviet-aligned Mongolia. Though officially termed an “incident” by Japan to avoid acknowledging a formal war, the conflict involved tens of thousands of troops, armor, artillery, and aircraft, making it the largest land battle Japan fought before the Pacific War. The fighting ended in a decisive Soviet victory, delivering a shock to the Japanese military and reshaping Japan’s strategic direction on the eve of World War II.

The Background

At the root of the conflict was a disputed, ambiguous border. Japan claimed the boundary lay along the Khalkhin Gol (Halha River), while the Soviets and Mongolians insisted it lay several miles east. The area was remote, sparsely populated, and economically marginal but symbolically important as a test of sovereignty and power. It was also extremely remote from the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) Staff and Ministry in Tokyo. All of this was simply ingredients of a toxic stew only awaiting the flame to start a boil. And the Kwantung Army was only too happy to ignite the flame.

The Kwantung Army had a well earned reputation for acting autonomously from Tokyo, initiating aggressive actions to force what it believed were the necessary political outcomes, and viewing itself as the vanguard of Japan’s continental destiny. This attitude led to the Mukden Incident (1931), the Marco Polo Bridge Incident (1937), and the quagmire of the Second Sino-Japanese War. By the summer of 1939 the IJA was already stretched thin, had terrible logistics support, and was lacking in combined arms capability – meaning tanks, artillery and ground support from aviation assets. Financially, Japan was stretched thin in trying to keep the IJA funded at the same time funding the Navy’s capital intensive shipbuilding efforts.

Nonetheless, by 1939 the bane of IJA’s existence – an independent, insubordinate junior officer corps believed that controlled escalation against the Soviets could secure Japan’s northern frontier, expand the strategic buffer or even open the door to expansion into resource-rich areas of Siberia. In the view of Japan, the majority of the peoples in Siberia and Mongolia were Asiatic and thus properly best served under the Imperial Protection of the Emperor. They did not bother to ask the people of those areas about their preference.

Northern Expansion Doctrine (Hokushin-ron)

Within Japan’s strategic debates, the Army strongly favored Hokushin-ron, the idea that Japan’s future lay in expanding northward against Russia rather than southward into Southeast Asia. This belief rested on overconfidence from victories in China, an underestimation of Soviet military modernization, and a deep seated anti-communism which was, at this time, being suppressed in the home islands. Nomonhan emerged from a belief that the Red Army could be tested, pressured, and defeated through limited engagement. It was less a grand strategy and more a tactical escalation.

In part it was also pushing back on the evolving southern expansion doctrine being proposed by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) whose interest lay in the resource-rich Southwestern Pacific, especially the oil fields of Borneo, Malay and Java.

The local IJA commanders were confident that Japanese infantry superiority would compensate for weaknesses in armor and logistics. In addition, they believed that the Soviets would avoid a major escalation. The Kwantung Army assumed that a sharp, localized victory would strengthen Japan’s hand diplomatically and militarily.

The IJA horribly misread Soviet intentions. The Soviets retained the memory of the humiliating defeat by Japan of czarist Russia. It was a lingering shame that the Soviets would never let happen again. They were more than willing to fight. They also had superior tanks and artillery and a capacity for combined arms operations with their ground forces. Japan also failed to recognize that the Soviets had the same essential “strategic buffer” view as Japan. Mongolia as part of that buffer and the Soviets would respond decisively to any threat in that region.

Combat

In the period May–June 1939, the initial clashes involved cavalry and infantry skirmishes for small areas of land as well as an island in the middle of the border river. Japanese forces crossed into disputed territory, driving out Mongolian units. Early successes reinforced Japanese confidence.

In June, the Soviets appointed General Georgy Zhukov to command. Zhukov rose to prominence with his leadership at Nomonhan. He was a brilliant tactician and field commander later becoming the most prominent and successful Soviet military commander during World War II often credited as the key strategist behind major Eastern Front victories against Nazi Germany. He rose to the position as Chief of the General Staff and a Marshal of the Soviet Union, leading the defenses of Moscow, Leningrad, Stalingrad and commanding the final assault on Berlin. He was formidable.

Long story, told short, Zhukov prepared a coordinated counteroffensive rather than piecemeal retaliation, amassing artillery, tanks, and aircraft supported by secure logistics/supply lines. In late August, Zhukov launched a classic double-envelopment, using tanks and mechanized infantry to encircle Japanese forces who lacked effective anti-tank weapons, were undersupplied, and relied on infantry assaults against armor. The result was catastrophic. Entire Japanese formations were destroyed or rendered combat-ineffective. It was a clear battlefield defeat involving some 20,000 Japanese casualties with the loss of experienced officers and elite units. Japan agreed to a ceasefire in September 1939, restoring the status quo but psychologically, the damage was done. It was the first unequivocal defeat suffered by Imperial Japan since the Meiji era.

Unintended Consequences

Nomonhan should have shattered Japanese assumptions – but it did not. Japan continued to believe that Japanese fighting spirit and bushido were enough to triumph and could overcome material inferiority and weak logistics. This would plague them all the way through 1945. They also continued to believe that wars could be tightly controlled and limited.

The defeat decisively undermined the Northern Expansion faction within the Army. After 1939 all plans for war against the Soviets were shelved, a defensive posture was adopted along the Manchurian frontier, and Japan avoided conflict with the Soviets for the remainder of WWII. This shift paved the way for Nanshin-ron (southern expansion), pushing Japan toward Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies’ oil. It was the path to confrontation with Western colonial powers. In this sense, Nomonhan helped set Japan on the road toward Pearl Harbor.

Perhaps the most profound unintended consequence was for the Soviet Union. Stalin gained confidence that Japan would not attack in the east and soon enough the two nations signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact (1941) allowing Soviet divisions to later be transferred west to defend Moscow against Germany. The Nomonhan incident influenced the outcome of the European war, not just Asian geopolitics.

The Nomonhan Incident stands as a warning ignored about the limits of aggression driven by ideology rather than sound political and military strategy and tactics. It revealed the dangers Clausewitz warned of: wars initiated for political symbolism without a clear path to decisive victory would ultimately end in disaster for those who initiated the action.

Nomonhan was not merely a border clash. It was Japan’s strategic crossroads. Historians have come to now recognize Nomonhan as one of the most consequential “incidents” of the twentieth century – even though it largely remains unknown in the West.

Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives. | Pacific area map of 1939 courtesy of MapWorks via Wikipedia Commons.