Depending on how one phrases and frames the question, one will arrive at different and often conflicting conclusions. While writing and posting the series on World War II in the Pacific (late August – early November, 2025) one of the recurring comments was that the United States started the conflict with its complete oil embargo on Japan on August 1, 1941. This followed the freezing of Japanese financial assets held in the United States during July 1941. Some folks asserted that those two actions were a blockade, which by international agreement is an act of war – hence the U.S. started the war.

There are two problems with that position. The first problem is that there is an important difference between a blockade and an embargo. A naval blockade is a military tactic where a belligerent power uses its navy to cut off a coastline or port, preventing all ships (enemy and neutral) from entering or leaving the nation under blockade. The intention is to stop supplies, trade, and communication, effectively starving the enemy’s war effort or economy. And yes, a blockade is indeed a recognized act of war under international law; an embargo is specifically excluded as an act of war.

In 1941 there were no U.S. naval forces operating in or around Japan. There were no restrictions on marine traffic in the western Pacific; Japan’s economic activities were unhindered for any nation that wished to trade with Japan. They were however finding that list of willing trading partners growing ever shorter given Japan’s aggressive expansion policies and military actions in the region.

And that leads us to the second problem. It is a completely myopic view to think war in the Pacific began on December 7, 1941. War in the Asia Pacific region was more than four years old with Japan being the provocateur and initiating agent in every instance. It is clear that the Asia Pacific War started in 1937 when the imperial ambitions of the nation of Japan launched military action against the nation of China, a conflict that some argue had started and been simmering since 1931. In previous posts we traced the rise of Japanese militarism that served as the agent of their colonial ambitions.

To be sure, the oil embargo was one of the dominoes in the chain. A few dominoes later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into the war as an active belligerent. The series to date followed the dominoes from the attack on the Hawaiian island of Oahu to the Japanese surrender in September 1945 – with few looks to events before that fateful day.

In case you are wondering about the phrase “the attack on…Oahu” it is good to remember that other installations were hit hard and suffered heavy casualties: Hickam Field, Wheeler Field, Bellows Field, Kaneohe Bay, and Schofield Barracks.

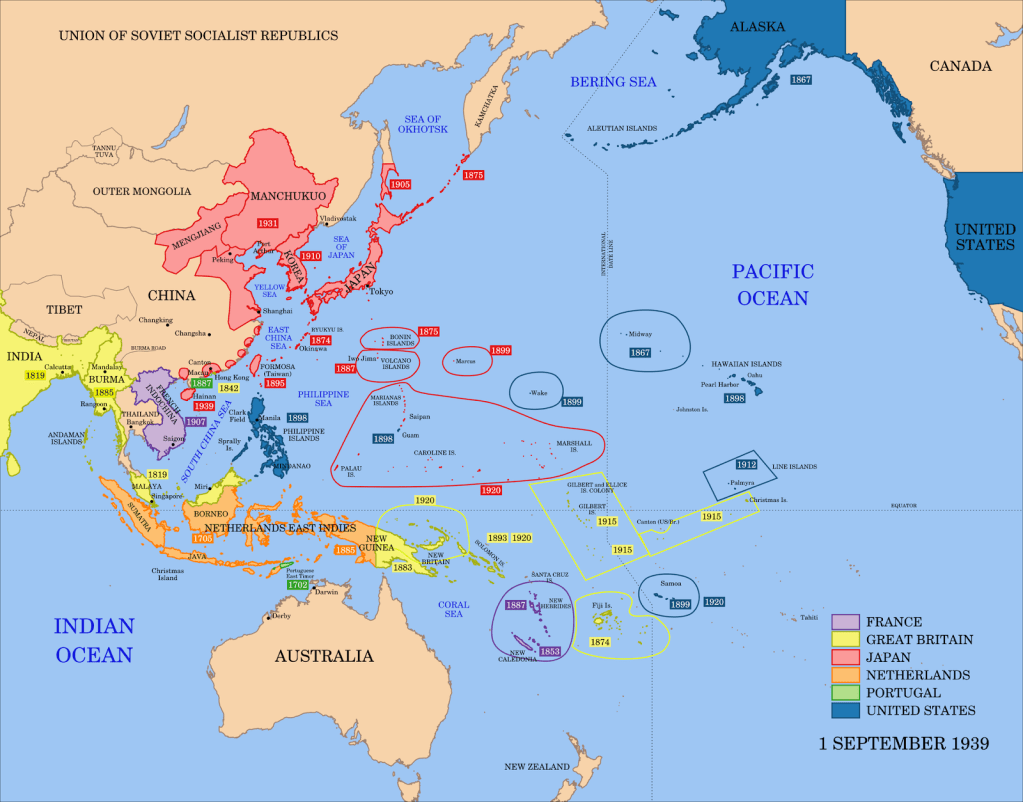

Long before December 1941, dominoes began to fall across the Asia Pacific region. China wasn’t the only nation that had been subjected to Japanese expansion. Japan had annexed Korea in 1910, taken over Manchuria in 1931 (setting up the puppet state of Manchukuo – that no nation recognized), and these are just two of the territories Japanese expansion had acquired by military means. Well prior to 1941, other nations included the Kingdom of Ryukyu (including Okinawa), Taiwan and the Penghu Islands, South Sakhalin, Saipan and Tinian in the Mariana Islands, the Marshall Islands, and the Caroline Islands. The following map shows the Asia Pacific region in September 1939 at the outbreak of war in Europe.

If the Dutch (Netherlands) East Indies and their oil field are the critical domino, you can see why French Indochina (Vietnam) was essential to the Japanese in order to secure and safeguard merchant shipping from the East Indies to Japan.. However, there are still two barriers in the way: (1) the U.S. Territory of the Philippines and (2) the British presence in Malaya, notably the major British port of Singapore. These two represented bases of operation that could interdict any marine traffic in the South China Sea and choke off critical supplies such as oil, rubber, and metals.

Without elaborating, let me simply say that there was great rivalry between the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). This rivalry had existed since before the start of the 20th century, ebbing and flowing in intensity. When the 1939 IJA forays into the border areas of Soviet controlled Mongolia and Siberia (the Nomohan Incident) were easily repulsed, Japanese attention and planning turned to the Southeastern Asia region – which had always been the strategic priority in the eyes of the IJN.

If Korea and Manchuria served as a food basket and new homesteads for an exploding Japanese home population, then Java, Malay, Borneo and other nations were seen as sources rich in oil, rubber, and other materials needed for Japan’s military-industrial complex. There was a strong sentiment among Japanese leaders that their national destiny was to be the rightful leader of the “Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” It was an ideology that was part of the education system and propaganda from the 1920s onward. The ideology was promoted as a means to free other Asian nations from the colonial rule of European nations, but in reality it was to establish themselves as the new colonial master. The underlying motivations for their territorial expansion was explored in a previous post, The Eight Corners of the World. In any case, the 20th century saw Japan transform itself from an island nation to an Asian Imperial Empire founded on military action.

Japan signed the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940, in Berlin, forming a military alliance with Germany and Italy as the primary Axis powers in World War II. The reasons were to deter the United States from intervening in Japan’s expansion in Asia, formalize its alliance with Germany and Italy, and establish distinct spheres of influence (Europe for Germany/Italy, Greater East Asia for Japan) for a new world order, all while securing mutual defense against potential attacks, especially from the U.S. and the Soviet Union (which Germany invaded on June 22, 1941)

At this point in time, France was fully occupied by German forces with the south of France (Vichy France) as a puppet government of the Nazis. In an arrangement with the Vichy government, Japan occupied the region of modern-day North Vietnam (French Indochina) starting in September 1940. At the same time Japanese troops began to encroach into “South Vietnam” (also part of French Indochina). By July 1941 Japan expanded its occupation to include all of South Vietnam. Another key domino in the chain fell.

The 1941 occupation of French Indochina was a tactical and strategic military move by the Japanese to position themselves to secure the Dutch East Indies oil fields and to control the sea lanes from those fields to the home islands for merchant shipping. The Japanese viewed the Dutch colonies as vulnerable since Germany had occupied Holland in May 1940. Although Holland was occupied the Dutch army, navy and air forces had not surrendered and were able and willing to defend its colonies and the oil resources. As well, the British military held strongholds in Singapore and Malaysia, bases from which to assist the Dutch, as well as to keep open Burma Road and its supply line to the Chinese fighting the Japanese invaders – and threaten the sea lanes to Japan.

The August 1941 oil embargo did not start the war. The war in the Asia-Pacific region was already underway. One only needed to ask the Chinese, Vietnamese and Mongolians, as well as the Koreans. The embargo was a calculated political action in reaction to the occupation of French Indochina. It was a political action whose hope was to deter Japan from further expansion. Nonetheless, one can ask:

- What was the background, purpose, and hope as regards the August 1941 oil embargo from the United States point of view?

- The U.S. understood the goals for Japan southwest incursion, but did the U.S. truly understand the underlying motivations?

- Was the embargo the decisive reason why Japan attacked Pearl Harbor or just more proximate than a collection of other reasons?

- Was the embargo a virtual declaration of war hoping to draw Japan to military action so that the U.S. could enter the war in Europe?

- Clearly the December 1941 and early 1942 “blitzkrieg” across Southeast Asia, the Southwest Pacific, and Central Pacific regions accomplished the mission of (a) capturing the resource rich nations and (b) setting a “line of defense” west of Hawaii – why did the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor? Couldn’t they just have left the sleeping giant alone?

But all of the above only leads to a larger question: how did the currents of history bring the U.S. and Japan to this point in history when sanctions and an embargo were the final domino that moved the flames of war to become the firestorm that was the Asia-Pacific War from December 1941 until September 1945? It is not just an interesting question in history. Consider the terms “sanctions”, “embargo”, “frozen financial assets” and others that are current in our news here in 2026. Are there lessons to learn from history?

Stay tuned.

Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.