This is intentionally a post for a Saturday morning. It is longer than average and traces the “history” of how historians have treated the year 1941 as regards U.S.-Japanese relationships. As with most things, even when historians can agree on the events and sequence of events, the role of historian is more than a news reporter. A historian’s role is to research, analyze, interpret, and write about the past. They gather and critically evaluate primary sources (letters, records, artifacts, photos) and secondary sources (other historians’ work). They then determine the authenticity, significance, and context of historical information to form a coherent understanding of events. The historian then constructs and writes detailed accounts, reports, articles, and books that tell the story of the past. In essence, historians are detectives of time, piecing together human history to make sense of the what, when, where of things in order to understand the “why.”

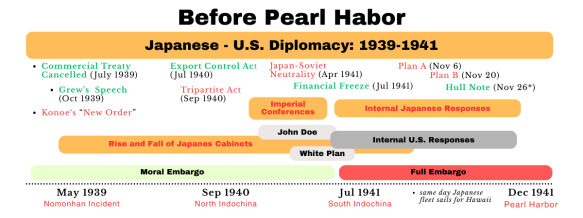

When considering a single event in history, such as the oil embargo, one quickly discovers it is not a single event. The event has people who are animating history with choices and decisions. The event has precursor events (which might need their own “histories”). The event is part of a chain of larger events, later events, and a complex web of factors large and small. All of this leads to different “schools of thought” among historians.

In the case of the 1941 oil embargo by the United States against Japan, there are the following schools of thought – interpretive camps, if you will:

- The Original Camp,

- The Provocateur Camp,

- The Coercion and Constraint Camp

- The Turning Point Camp

- The Contemporary Camp

These names are my own and (hopefully) offer a reasonably accurate 30,000 ft view of the positions. Over simplification and errors are mine, and so apologies in advance to the historians referenced if I have misunderstood or misinterpreted their work.

The Original Camp were the first wave of historians such as Herbert Feis and Samuel Eliot Morison who wrote in the later 1940s and early 1950s. As they were first to publish their work formed an initial orthodoxy regarding the oil embargo. Their conclusions were that Japan was solely responsible for the U.S. entry into the war. They judged U.S. policy to be defensive and reactive to Japan’s provocation with the ultimate treachery being the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the island of Oahu, Hawaii.

The work did not address prior U.S. economic sanctions and actions, internal policy debates within the U.S. State department and regulatory agencies, external policy debates with Britain over support and prosecution of the already on-going war in Europe, North Africa, and in the steppes of Russia.

The work did not have the available resources, and as such insufficient attention was paid to the internal dynamics of Japanese governance which was divided among the militarism and the moderates – with Emperor Hirohito seemingly passively on the sidelines. The treatment of the internal Japanese governance is as though it were monolithic when it was anything but. As a result there was limited consideration of internal Japanese deliberations which caused Japanese diplomatic responses and actions to appear opaque, intentionally vague, and even deceptive. In parallel, these authors were not insightful or critical of U.S. diplomacy which seemed blunt and imperious to the Japanese. There is very little recognition of U.S. errors in policy or decisions.

Lastly, given the period in which they worked, they relied almost entirely on U.S. sources.

The Provocateur Camp argues that U.S. policy made war so likely as to make war unavoidable regardless of who fired the first shot. In historiography circles, they are known as the “Revisionists.” I am not a fan of that title in this particular case as “revisionists” often just refers to the next generation with access to additional source materials. In this case, “Provocateur” seems the better moniker. Historians that I would place in the category include Charles Beard and Charles Tansill who published in the period 1950-1956. While they had some new materials, like all historians of their age they lacked access to all the classified war information that was only made available to researchers in 1995. While different in content, these writers contend that President Roosevelt deliberately maneuvered Japan to the brink of war knowing sanctions and embargoes were provocative.

While neither entertain the “Roosevelt knew Pearl Harbor would be attacked and did nothing” theory. They both hold Roosevelt and his cabinet as the provocateurs of the war. They conclude that Roosevelt knew the U.S. entry into the war with Germany was inevitable, and so used Japan as the “back door” to enter into the global conflict. Roosevelt’s concern was fascism’s (Germany. Italy, and Japan) deconstruction of liberal governmental and economic policies resulting in a new “dark ages” for the world order. The oil embargo was a virtual declaration of war as U.S. leadership understood Japan could not accept the embargo without collapsing as a power in the Asia-Pacific region where the U.S. had traditional trade and business interests. The weakness of this historical view is that it glosses over Japan’s “power” and, in effect, downplays the raw military aggression Japan had waged throughout the 1930s into the 1940s.

The Coercion and Constraint Camp are less conspiratorial but argue that U.S. actions left Japan with no acceptable alternatives. Writers such as William Williams and Gabriel Kolko might be considered part of this school of thought, writing in the period 1959-1968 – again researching in an age before the declassification of WW II records. A later work by Sidney Pash (2014) revisits some of the same archival information, but unlike Williams (an economic determinist), Pash emphasizes more traditional diplomatic concepts such as the balance of power and containment.

The principle argument is that the U.S. spoke of an open door policy of trade and commerce in the Asia Pacific region, but the real goal was a type of benign imperialism under the guise of open markets and free trade. It is argued that the U.S. insistence of principles such as respect for national boundaries, respecting the sovereignty of other nations, not interfering in other nations internal politics, and openness to trade and commerce failed to acknowledge the Japanese strategic realities of a lack of natural resources, burgeoning population, and a view of themselves as the rightful leader of the Asia-Pacific region.

In general this camp does not excuse Japanese aggression, but sees the U.S. as implementing systematic coercion and constraints to control events in the region. One view is that the U.S. did not realize the effects of systematic coercion and constraints they were attempting to put into play – nor the Japanese reactions to them. Unlike the “Provacteur Camp” there is no conspiracy to start conflict. It is more of a clumsiness and bias in operating the available levers of power. But like their historiographical elders, they too gloss over the manner in which Japan projected power, paying little attention to the rise of militarism and nationalism that were the drivers behind their naked invasion of other countries, and just seem to ignore that no Asia-Pacific nation wanted their leadership. Some work focuses only on diplomatic encounters of the moment while paying scant attention to other internal elements. A good example is the treatment of the 1922 Washington Conferences and naval limitation treaty. The conclusion reached is that the U.S. and Britain (two-ocean navies) were trying to control Japan’s shipbuilding projects (one-ocean navy) without ever mentioning that other than the military, the rest of Japan’s governance welcomed the limitation because they wanted to avoid an arms race they couldn’t afford while in the midst of their own financial crises.

The Turning Point Camp largely wrote in the late 1980s. Some consider this as an extension of the Revisionists Camp. Writers include Jonathan Utley, Waldo Heinrichs, and Akira Iriye. These historians focus on July-August 1941 as the turning point of the pre-Pearl Harbor period after which war between Japan and the United States was a given. Their focus is largely upon diplomacy and the currents of power/views within Washington DC and Tokyo. This group of writers had the advantage of access to non-military documents, war time diaries, translated Japanese documents, memoirs of key actors, and correspondence in the arena of governance and diplomacy. These were resources not available to previous historians.

A compilation of the central tenet of this camp might be captured in the problem of disinstantiated communication. In other words, “that’s not what I meant!” vs. “but that’s what I understood.” This was fueled by preconceptions, misconceptions, and presumptions of “national character.” And in some cases, the barrier of language and cultural norms. As a result, the actions and understandings were miscalculations rather than conspiracy. The “Hull Note” in late November 1941 is an example of such. Although it should be noted that Kido Butai, the Japanese fleet that attacked Peart Harbor, had already set sail, battle plans in hand, and under strict radio silence.

While acknowledging these shared problems, this camp finds fault with U.S. policymakers who:

- underestimated Japanese willingness to fight,

- overestimated the impact of embargoes and trade sanction on Japanese military and economic collapse

- insisted on principles Japan could not accept without abandoning its empire, making war likely,

- Did not realize that there was a “manifest destiny” operative in the politicized Shinto myth of the “eight corners of the world”

- did not recognize that their (U.S.) actions were escalatory in effect,

- were unwilling to compromise, and

- assumed Japan would eventually back down.

Instead, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and across the Southwest Asia region as a response to constraints applied by the U.S. These historians acknowledge that Japanese military aggression in the region over the decade was a war already begun. Their view is that the U.S. did not force Japan to attack Pearl Harbor, but it pursued policies attempting to control Japanese aggression that increased the probability that the U.S. would be drawn into armed conflict with Japan.

The Contemporary Camp is the current era of historians (e.g., Sadao Asada, Richard Frank) share a view with the “Original Camp” that holds Japan fully and wholly culpable for the Asia-Pacific War, but also recognize elements and nuance of the “Turning Point Camp.” What is different is the trove of new materials that have been made available, especially Japanese language sources, diaries, letters, previously unknown documents. They are more attentive to the chaotic rise and fall of Japanese cabinets, the veto power of the military, the popular support for the Japanese military, and the increasing alignment with fascist ambitions in the region.

These later historians are much more balanced in understanding the role of Nazi Germany in Roosevelt’s thinking. FDR understood that the U.S. was in no way prepared to enter war with Germany (which was the priority) much less war with Germany and Japan. What industrial capacity was available was geared to keep Britain “in the fight” as well as the Soviet Union (which Germany attacked in later June 1941).

While recognizing the impact of the “oil embargo”, these historians are more likely to call the timing of and the attack on Pearl Harbor the turning point in the broader was for these reasons:

- On December 5tn, the Soviets began a massive counter-attack on German forces at Moscow and attacks across a broad front in other regions. The strength and impact of this would not be known to Hitler for several weeks.

- Japan “declared war” on by the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941

- Germany formally declared war on the United States on December 11 in accord with the Tripartite Pact

- By Dec 16th, Hitler was aware of the seriousness of the Soviet’s advances.

If Pearl Harbor had been planned for January 1942, realizing the problems on the German eastern front, would Germany have declared war on the United States? An interesting counter-factural, but the point is the broader view held by these historians.

Image credit: various photographs from Naval Aviation Museum, National World War II Museum, and US Navy Archives.

Did you know that nearly one quarter of McDonald’s Filet-of-Fish sandwich sales take place during Lent, when many fast-food customers are abstaining from meat? “That’s exactly what the McDonald’s operator who first put the cheese-topped sandwich on his menu had in mind back in 1962. When Cincinnati McDonald’s franchise owner Lou Groen noticed that his heavily Catholic clientele was avoiding his restaurant on Fridays, he suggested to McDonald’s owner Ray Kroc that they add introduce a fish sandwich. That led to a wager between Groen and McDonald’s chief Ray Kroc, who had his own meatless idea. “He called his sandwich the Hula Burger,” Groen said. “It was a cold bun and a slice of pineapple and that was it. Ray said to me, ‘Well, Lou, I’m going to put your fish sandwich on (a menu) for a Friday. But I’m going to put my special sandwich on, too. Whichever sells the most, that’s the one we’ll go with.’ Friday came and the word came out. I won hands down. I sold 350 fish sandwiches that day. Ray never did tell me how his sandwich did.”

Did you know that nearly one quarter of McDonald’s Filet-of-Fish sandwich sales take place during Lent, when many fast-food customers are abstaining from meat? “That’s exactly what the McDonald’s operator who first put the cheese-topped sandwich on his menu had in mind back in 1962. When Cincinnati McDonald’s franchise owner Lou Groen noticed that his heavily Catholic clientele was avoiding his restaurant on Fridays, he suggested to McDonald’s owner Ray Kroc that they add introduce a fish sandwich. That led to a wager between Groen and McDonald’s chief Ray Kroc, who had his own meatless idea. “He called his sandwich the Hula Burger,” Groen said. “It was a cold bun and a slice of pineapple and that was it. Ray said to me, ‘Well, Lou, I’m going to put your fish sandwich on (a menu) for a Friday. But I’m going to put my special sandwich on, too. Whichever sells the most, that’s the one we’ll go with.’ Friday came and the word came out. I won hands down. I sold 350 fish sandwiches that day. Ray never did tell me how his sandwich did.”