I am grateful for a day in which we, as a people, pause to give thanks. And who do we have to thank for this holiday? Your answer is likely “The Pilgrims.” You would not be wrong, but then not completely correct, either. Certainly, Thanksgiving and the religious response of giving thanks to God is as old as time. When one considers enduring cultures, one always finds men and women working out their relationship to God. There is almost always a fourfold purpose to our acts of worship: adoration, petition, atonement, thanksgiving. Such worship is part and parcel of life. And yet, there is still a very human need to specially celebrate and offer thanksgiving on key occasions and anniversaries. Since medieval times, we have very detailed records of celebrations marking the end of an epidemic, liberation from sure and certain doom, the signing of a peace treaty, and more. Continue reading

Woe to the soul

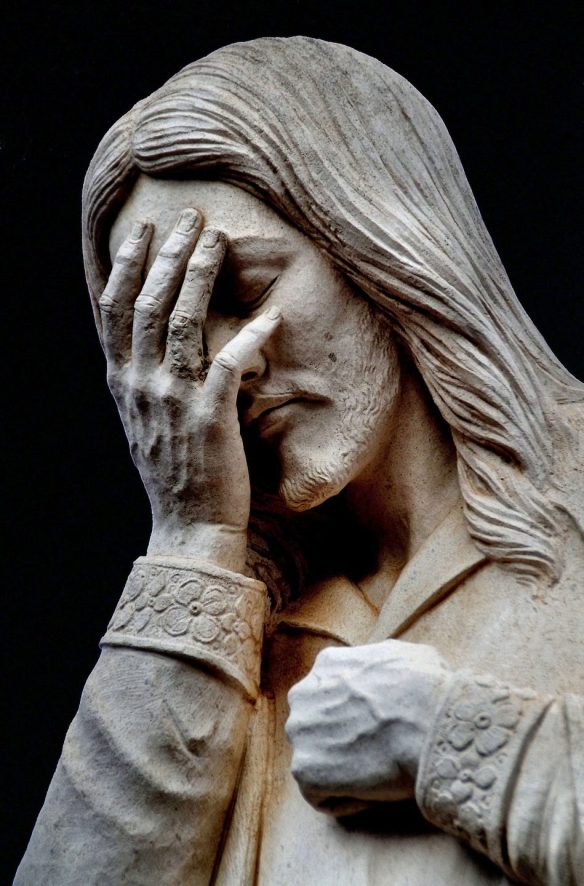

From the Office of Readings for the Day – a homily attributed to Saint Macarius, bishop (Hom. 28: PG 34, 710-711). A note: while we often think of the word “woe” as pertaining to accusation and condemnation, the biblical meaning is most often as a lament, a sadness or mourning over an instance or circumstance.

Woe to the soul that does not have Christ dwelling in it

And Jesus wept…

When God was displeased with the Jews, he delivered Jerusalem to the enemy, and they were conquered by those who hated them; there were no more sacrifices or feasts. Likewise angered at a soul who had broken his commands, God handed it over to its enemies, who corrupted and totally dishonored it. When a house has no master living in it, it becomes dark, vile and contemptible, choked with filth and disgusting refuse. So too is a soul which has lost its master, who once rejoiced there with his angels. This soul is darkened with sin, its desires are degraded, and it knows nothing but shame.

Woe to the path that is not walked on, or along which the voices of men are not heard, for then it becomes the haunt of wild animals. Woe to the soul if the Lord does not walk within it to banish with his voice the spiritual beasts of sin. Woe to the house where no master dwells, to the field where no farmer works, to the pilotless ship, storm-tossed and sinking. Woe to the soul without Christ as its true pilot; drifting in the darkness, buffeted by the waves of passion, storm-tossed at the mercy of evil spirits, its end is destruction. Woe to the soul that does not have Christ to cultivate it with care to produce the good fruit of the Holy Spirit. Left to itself, it is choked with thorns and thistles; instead of fruit it produces only what is fit for burning. Woe to the soul that does not have Christ dwelling in it; deserted and foul with the filth of the passions, it becomes a haven for all the vices.

When a farmer prepares to till the soil he must put on clothing and use tools that are suitable. So Christ, our heavenly king, came to till the soil of mankind devastated by sin. He assumed a body and, using the cross as his ploughshare, cultivated the barren soul of man. He removed the thorns and thistles which are the evil spirits and pulled up the weeds of sin. Into the fire he cast the straw of wickedness. And when he had ploughed the soul with the wood of the cross, he planted in it a most lovely garden of the Spirit, that could produce for its Lord and God the sweetest and most pleasant fruit of every kind.

Image credit: Flevit super illam (He wept over it) | Enrique Simonet (1892) | Museo del Prado, Madrid | Wikimedia Creative Commons

Even if the end is delayed

This coming Sunday is the first Sunday in Advent. In the posts from yesterday we reviewed the context of the gospel as used in Advent and in the larger context of a unified gospel. In today’s post we pick up the idea that Matthew’s primary concern is pastoral so that the community continues in its discipleship even if the end is delayed.

John Meier (Matthew,291) notes that a good part of Ch. 24 in Matthew is spent in attempting to calm off-based eschatological (end-time) fervor and calculation. Something that even in our day has become a cottage industry as folks pore over Daniel and Revelation attempting to “crack the code” about the end-time when/where. The three rapid-fire parables in our gospel reading attempt to establish a proper eschatological fervor (watchfulness). The three parables (the generation of Noah, the two pairs of workers, and the thief in the night) announce the major theme of the second part of the discourse: vigilance and preparedness for the coming [parousia] of the Son of Man.

Continue readingPassing Things; Permanent Things

Today’s readings place before us two very powerful images of history. In the first reading from the Book of Daniel, is the scene in the Book of Daniel when he is asked to interpret a dream of King Nebichadnezzar. In the dream there is a statue of gold, silver, bronze, iron, and clay; understood as giant empires rising and falling. In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus foretells the destruction of the Temple, a building so magnificent that people were “admiring how it was adorned with costly stones” (Lk 21:5). In both readings, we are reminded of the fragility of earthly things, passing things – even the things we think are permanent

All earthly kingdoms pass away. Daniel interprets Nebuchadnezzar’s dream: a statue of dazzling appearance, representing the great powers of the world. But Daniel also says: “A stone was hewn from a mountain without a hand being put to it… and it struck the statue… and crushed them” (Dan 2:34–35). And then Daniel gives the meaning: “The God of heaven will set up a kingdom that shall never be destroyed… it shall stand forever” (Dan 2:44).

Empires rise; they fall. New powers come; they fade. What looks permanent at the time ends up being temporary. We need that reminder today: nothing in this world—no nation, no power, no economy, no institution—is eternal. Only the kingdom of God lasts.

We are not to be dazzled by earthly splendor. In the Gospel, some people marvel at the beauty of the Temple. It was truly magnificent—one of the wonders of the ancient world. But Jesus says: “The days will come when there will not be left a stone upon another stone that will not be thrown down” (Lk 21:6). Even the Temple, the holiest place in Israel, would fall. Jesus is not trying to frighten us. He is trying to reorient us. He is reminding us that beauty and power are not the same as holiness and eternity. God invites us to place our trust not in the structures or successes of this world, but in Him alone.

Because God’s kingdom is already breaking into our world. When the stone in Daniel’s vision strikes the statue, Daniel says: “The stone… became a great mountain and filled the whole earth” (Dan 2:35). The Fathers of the Church saw this stone as a symbol of Christ. The Cornerstone rejected by the builders, yet chosen by God. And so Christ’s kingdom has already begun in His death and resurrection. And even as nations rise and fall, even as there are “wars and insurrections… earthquakes, famines, and plagues” (Lk 21:9,11), the kingdom of God continues to grow quietly, steadily, like a mountain that fills the earth. Not through force. Not through power. But through the holiness of God’s people, through the sacraments, through acts of mercy, forgiveness, and love.

What does this mean for us today? It means that the Christian life is not about predicting the end, nor about reading the “signs” with fear. Jesus specifically says: “Do not be terrified” (Lk 21:9). We don’t follow Christ to secure ourselves against worldly catastrophes. We follow Him because He alone is the kingdom that does not pass away.

So the question for us today is simple: Where is my heart anchored? In the things that pass away—or in the One who stands forever? When our hearts are anchored in Christ, even the storms of history cannot shake us. Even when earthly certainties collapse, our hope remains firm.

The great empires of Daniel’s vision are long gone. The stones of the Temple Jesus described have long since fallen. But the kingdom of Christ endures. And we are invited to belong to that kingdom—now, today, in this Eucharist.

May the Lord give us the wisdom to cling to what is eternal, to seek first the kingdom that “shall never be destroyed” (Dan 2:44), and to live unafraid, trusting in the One who reigns forever.

The One who is King of the Universe.

Image credit: Flevit super illam (He wept over it) | Enrique Simonet (1892) | Museo del Prado, Madrid | Wikimedia Creative Commons | PD-US

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream

The first reading today is the scene in the Book of Daniel when he is asked to interpret a dream of King Nebuchadnezzar. In the world of eschatology (the part of theology concerned with death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of humankind) this is one of the passages that fascinates all manner of interpretation

Key verses in the dream are:

- “You are the head of gold.” (Dan 2:38)

- “Another kingdom shall rise after you… then a third… then a fourth kingdom, strong as iron.” (Dan 2:39–40)

- “A stone which a hand had not cut from a mountain struck the iron, the clay…” (Dan 2:34)

- “The God of heaven will set up a kingdom that shall never be destroyed.” (Dan 2:44)

Summary Table of Understanding of Key Elements

| Tradition | Four Kingdoms | Stone / Mountain |

| Rabbinic Jewish | Babylon, Media, Persia, Greece | God’s final kingdom / restoration of Israel |

| Patristic Christian (2nd-5th century AD) | Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, Rome | Christ / Church / eternal kingdom |

| Modern Critical (Protestant & Reformed) | Babylon, Media, Persia, Greece | God’s intervention after Antiochus IV |

| Dispensational Futurist (Evangelical etc.) | Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, Rome → revived Roman empire | Christ at Second Coming, millennial kingdom |

| Catholic | Either traditional (Rome) or historical-critical (Greece) | Christ’s kingdom, both present and future |

These verses and its elements form a basis of a “dispensational” view of time. In this context, the “dispensations” are times in history vis-a-vis the Kingdom of God. When considered from an eschatology perspective there are some basic questions, whose answers means that “dispensationalism” is not monolithic. Differences appear when when discerning if the “Kingdom” is now, even if only partially revealed; does the visible Church on earth represent (or even part of) the Kingdom; what are the four empires; what is the relationship of kingdom of the 2nd Coming of Jesus; and the list goes on…

Within Dispensationalism there are distinct schools of interpretation of Daniel 2 (and prophetic texts generally). They agree on certain basics—the four kingdoms end with a revived Roman empire, the stone is Christ at His Second Coming, the Church is not the kingdom of Daniel 2, etc.—but there are real differences.

| Dispensational View | Stone = Christ’s Kingdom? | Is It Already Present? | Ten Toes? | Church in Daniel 2? |

| Classical | Second Coming only | No | Literal 10 kings | No |

| Revised/Modified | Second Coming | No (or partial) | Literal or symbolic | No |

| Progressive | Inaugurated now, fulfilled later | Yes (but not fully) | Symbolic for final rulers | No |

| Apocalyptic Literalist | Dramatic Second Coming | No | Literal 10-nation confederacy | No |

| Two-Phase Roman Empire | Second Coming | No | Literal or flexible | No |

A view of Matthew’s End Time

This coming Sunday is the first Sunday in Advent. In an earlier text from today, we introduced the two-fold character of Advent. In this post we consider Matthew’s perspective of the End Time. The post is on the longer side and deals more with the text in a larger context and less so about its use in Advent.

Eugene Boring (Matthew, 457-58) notes Matthew 24 is not an “eschatological discourse” that presents Matthew’s or Jesus’ doctrine of the end, but is part of chaps. 23-25, whose aim is pastoral care and encouragement. Although he has included the “little apocalypse” of Mark 13 into this larger framework, Matthew (affirms but) reduces the significance of apocalyptic per se, subordinating it to other, more directly pastoral concerns. Matthew’s focus is judgment and warnings on Christian discipleship oriented toward the ultimate victory of the reign of God represented in Christ.

Matthew focuses on this by a variety of pictures that are sometimes at odds and sometimes in agreement. No one picture can do justice to the transcendent reality to which it points. There are basically two types of pictures:

- In the first of these, the risen Christ is present with his church throughout its historical pilgrimage and mission. Matthew affirms the transcendent lordship of the living Christ. This is expressed in pictures of Christ’s continuing presence with his church through the ages, a major theme of Matthean theology (see 1:23; 28:20). In such a framework, there is no need or room for an ascension in which Christ departs, a period of Christ’s “absence,” and then a “return” of Christ, for the risen Christ never departs (cf. the last words of Matthew’s Gospel).

- In a second type of picture, the transcendence of the living Christ is pictured in a different way that had already become traditional in early Christianity—that of the departure of Christ at the resurrection/ascension and his return at the parousia.

The Vietnamese Martyrs

“Beware of men, for they will hand you over to courts and scourge you in their synagogues, and you will be led before governors and kings for my sake as a witness before them and the pagans” (Mt 10:17-18)

Today we celebrate the martyrdom of Fr. Andrew-Dung-Lac and Companions. The title of the memorial is a bit misleading – its title follows the tradition of the General Roman Calendar. But in other places and times the name of the celebration is known as a feast dedicated to the Vietnamese Martyrs, the Martyrs of Annam, the Martyrs of Tonkin and Cochinchina, or the Martyrs of Indochina.

What is being remembered today is perhaps the most deadly of all Catholic persecutions. During a period from 1745-1862, the Vatican estimates that 300,000 to 400,000 of the faithful were martyred.The final 30 years were particularly brutal. There are 117 names that are known, and alphabetically Andrew Dung-Lac begins the list.

The letters and example of Fr. Théophane Vénard (Paris Foreign Mission Society) inspired the young Saint Thérèse of Lisieux to volunteer for the Carmelite nunnery at Hanoi, though she ultimately contracted tuberculosis and could not go.

The tortures these individuals underwent are considered by the Vatican to be among the worst in the history of Christian martyrdom. The torturers hacked off limbs joint by joint, tore flesh with red hot tongs, and used drugs to enslave the minds of the victims. Christians at the time were branded on the face with the words “tả đạo” meaning “sinister religion”. Families and villages which professed Christianity were obliterated. “The souls of the just are in the hand of God, and no torment shall touch them. (Wisdom 3:1).

When I read of the faithful and heroic people such as these, I often recall the words of St. Francis of Assisi: “It is a great shame for us, the servants of God, that the Saints have accomplished great things and we only want to receive glory and honor by recounting them.” (Admonition 6)

Pope John Paul II canonized the 117 martyrs together on June 19, 1988. At the time, the Vatican said, the communist government of Vietnam did not permit a single representative from the country to attend the canonization. But 8,000 Vietnamese Catholics from the diaspora were there, “filled with joy to be the children of this suffering Church.” (Catholic News Agency)

Image credit: This work of art was displayed at St. Peter’s on the occasion of the Vatican’s Celebration of the Canonization of 117 Vietnamese Martyrs on July 19, 1988. | Credit: Public domain

Come and Come Again

This coming Sunday is the first Sunday in Advent and the first Sunday of the new liturgical year, Cycle A, in which the Gospel of Matthew is the anchor text for the next 12 months. The readings are not very “Chrismassy” nor are they intended to be. Advent is a different season. Advent has a two-fold character: as a season to prepare our hearts for Christmas when Christ’s first coming is remembered with joy and as a season when that remembrance directs the mind and heart to await Christ’s second coming at the end of time. Advent is thus a period of devout and joyful expectation with an element of repentance as part of the preparation.

The readings for the First Sunday of Advent serve as a transition from the celebrations of Christ the King Sunday into the new year. The readings are replete with a strong theme of “staying awake” and being “prepared” for the days to come when the promises to Israel will be fulfilled.

This text is part of the fifth discourse in Matthew (24:1-25:46), which centers on the coming of the Son of Man – and that does not necessarily imply “end times” as in end-of-the-world. The theme for the 1st Sunday in Advent (for all three years) is preparedness – in the everyday of life as well as for the end of life. What is common to all times is the victory of the reign of God.

Continue readingThe King We Choose

Kings are an interesting concept. When someone tries to impose their will upon us, one of our tried-and-true responses is, “Who died and made you king?” Maybe our American spirit has a bias against unbridled power in the hands of the one. Yet there is something within us that wants a king when we want a king – you know – the times we feel uncertain, times are turbulent, and we are just a tad frightened. Like the people of Israel at a pivotal point in the Old Testament. The people come to the prophet Samuel and demand that he ask God to send them a king so that they could be, not the people of God, but that they could be like the people in the nations around them. It seemed to the Israelites that those people were secure, safe and prosperous.

Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Joshua – some of the great names of Israel’s history and none of them were kings. Yet under the leadership of God, they led Israel from slavery to the freedom of the promised land. Deborah, Gideon, Samson – none of them were kings, yet under the leadership of God, these Judges united Israel to defend itself and its identity as a people chosen by God. When the people asked the Prophet Samuel to ask God to give them a king, Samuel understood the implications: the people thought that the Lord God wasn’t doing such a good job. The people wanted a different king. They wanted to be people other than who they were called to be: the people of God.

The people wanted a king who could offer security against enemies foreign and domestic. A king who would promise a better tomorrow, a prosperous future, and make us feel better about our lives. A king who would ensure we will not be threatened, face risk, or suffer. The people of Israel wanted a king that projected power, invulnerability, and a better tomorrow. That better tomorrow never came under the kings of Judah and Israel who were largely self-absorbed tyrants. The times were always turbulent, the future was always just around the corner, and after 400 years, there was no king – and the people of Israel were enslaved in exile in Babylon. So much for kings. Be careful what you ask for.

Interestingly, our ancestors fought a revolutionary war to throw off the burden of kings in order to live free. As a political people we want no king. But what about as a people of faith? Of course, the answer is “yes” because on this day we celebrate “Christ the King Sunday!”

We are a nation dedicated to the proposition that we need no king, and yet there are times when I wonder if we Christians are not too dissimilar from the Israelites of old and we too want to be like other people and follow the kings of fashion and fame, lifestyle and licentiousness, and, power and politics. The Solemnity of Christ the King is to remind us to daily choose the king we would follow.

What kind of king is Christ the King?

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.

He is the head of the body, the church.

He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead,

[who] reconciled all things …, making peace by the blood of his cross

Jesus is a king like no other:

- He has no scepter but only towel to wash his disciples’ feet

- He wore no crown of gold but one of thorns

- His royal courtyard was a place called the Skull. His courtiers were a criminal on his left and a criminal on his right.

- His royal court was not a place of judgment and execution for those who contested his power, but a place where forgiveness was found

- The King was not separated from the people by a security team, but he walked, spoke and shared the life of his people, like us in all things except sin

- The King of Kings did not entertain only the nobility and powerful. He shared table with the sinners, the prostitutes, tax collectors, widows, orphans, foreigners, and thieves.

- His kingdom’s boundaries do not delineate, separate and marginalize. Rather his rule and grace extend to prodigals, the Samaritans, the poor and outcast, the lepers, and to all the world

- The King did not impose his power, he proposed his grace and mercy

- The King did not lay the debts of his monarchy on the backs of his people, he laid down his own life so that the debt of human sin would be forgiven

- He did not wield the sword of war and conquest but preached the good news that can quell the wars that rage within us and around us

- The King reconciled all things …, making peace by the blood of his cross

He is not like other kings and yet he is King of the world. “In him were created all things in heaven and on earth, the visible and the invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or powers; all things were created through him and for him.” Perhaps better said, King of Hearts – every heart, for the desire of God is that all be saved.

And what about us? We are like the people who came before the Prophet Samuel – each day we are at a personal tipping point. Do we want to be like the people of the other nations, subject to other kings or will we pray for the grace to be members of God’s kingdom? Will we distort the kingdom with sin, selfishness or diminish it with our pride and prejudices? Will we stand with the powerful and entitled, or will we stand with those of the margins?

If this is the king we want, then we are called to follow and love with our whole life, our entire being. If we choose to follow the King of All Hearts, we are choosing to reflect his image and inherit all the rights of his kingship. We need not look for a scepter with which to rule over others, but only need to look for a towel with which to serve. Not condemn but extend mercy and forgiveness. We must choose to make the King’s virtues our own – so that others will recognize the King and that we belong to Him, the King of All Hearts.

Image credit: Stained glass window at the Annunciation Melkite Catholic Cathedral in Roslindale, Massachusetts, depicting Christ the King in the regalia of a Byzantine emperor CC-BY-SA 3.0; January 2009 photo by John Stephen Dwyer

Amen

This coming Sunday is the celebration of the Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. In yesterday’s post we considered those executed alongside him – the two thieves. Today we conclude our study and consider

“Amen, I say to you” is the sixth time Luke has used this phrase and the only one addressed to one person. It is also the last of the emphatic “today” pronouncements. Like the poor, the crippled, the blind, and the lame in Jesus’ parable of the great banquet (14:21), the thief would feast with Jesus that day in paradise. Like Lazarus who died at the rich man’s fate (16:19-31), the thief would experience the blessing of God’s mercy.

St Paul wrote:

For if the dead are not raised, neither has Christ been raised, and if Christ has not been raised, your faith is vain; you are still in your sins. Then those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are the most pitiable people of all. But now Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead came also through a human being. For just as in Adam all die, so too in Christ shall all be brought to life (1 Cor 15:16-22)

In Luke’s own way, the promise to the penitent thief reflects this same idea. Others taunted Jesus, mocking him with challenges to save himself, so with fitting irony his last words to another human being are an assurance of salvation. Jesus’ ministry has been focused on the widow, the tax collector, the outcast, the foreigner, the poor and destitute, and any number of monikers for those people on the margins of life. Jesus began the ministry proclaiming “good news to the poor” and “the release of captives” (4:18) – and he ended the ministry by extending an assurance of blessing to one of the wretched.

“…today you will be with me in Paradise” The promise is that the criminal would be “with Jesus” in paradise. Jesus’ close association with sinners and tax collectors that was part of his life, is also part of his death and his life beyond death. The word “paradise” (originally from Persia) meant “garden,” “park” or “forest”. The Greek paradeisos was used in the LXX for the “garden” in Eden, the idyllic place in the beginning where the humans walked and talked with God. Isaiah presents the “garden/paradise” of Eden as part of the future salvation (53:3).

Later, some groups within Judaism considered paradise to be the place where the righteous went after death. Paul considered paradise to be in the “third heaven” (2Cor 12:4). Revelation has the tree of life in the “paradise of God” (2:7). In later chapters the tree of life seems to be located in the new Jerusalem that has come down from heaven (22:2,14,19).

Perhaps as with basileia, we should think of paradeisos as something other than just a place – perhaps as a restored relationship with God.

Image credit: Stained glass window at the Annunciation Melkite Catholic Cathedral in Roslindale, Massachusetts, depicting Christ the King in the regalia of a Byzantine emperor CC-BY-SA 3.0; January 2009 photo by John Stephen Dwyer